Exclusive Excerpt: Ed Helms & that time the CIA tried to steal a submarine

Plus: Ed & Rainn reunite on the podcast!

Greetings, O Nard Dogs of Light!

This week, we’re excited to share a reunion between two real-life friends and iconic Dunder Mifflin frenemies: Rainn and Ed Helms.

Watching these Officemates reconnect, the joy and ease of old friendship shone through—built on years of laughter, wild plotlines, and trailer snacks. But they didn’t just reminisce. They got real—on ADHD, mental health, and the quiet brilliance of being “a fool” (in the best way).

After the recording, we lingered. Ed mentioned someone had asked what he feels watching old clips of The Office. His answer? “Honestly… I just see how happy I was.” Not fame. Not pressure. Just joy.

One of us said, “That’s perfect, since your most famous line is, ‘I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days before you’ve actually left them.’” Ed smiled. “Yeah. That’s exactly what it was.” We joked, “Dang! I wish we got that in the recording.” Ed replied, “Not everything’s for the internet.”

He’s right. May your best moments happen offscreen—in those sacred, messy, unseen spaces where no one’s filming.

But let’s be honest: the internet is with us for good. And the moments that teach, inspire, or remind us of our shared humanity? They’re not always what the algorithm serves first. Too often, it’s noise, conspiracy, outrage. Ironically, with so much real injustice in the world, we don’t need fake conspiracies—especially the kind that scapegoat the vulnerable while shielding real malefactors.

Even when we can’t fully name what’s wrong, that gut sense that something’s broken isn’t wrong. We just need depth over easy outrage.

Which brings us to Ed’s latest project: SNAFU—both a podcast and a new book. It’s the perfect tonic: insightful, hilarious, and sneakily wise. Why the title? SNAFU is a WWII acronym for Situation Normal: All Fucked Up. As Ed puts it: “the soldiers who coined it were essentially saying, “Yeah, everything’s a disaster—but hey, isn’t it always?” Over time, the term traveled beyond the battlefield and made its way into our everyday language. Today, according to Oxford Dictionaries, SNAFU means “a confused or chaotic state; a mess.” A definition that, frankly, could apply to everything from assembling IKEA furniture to your last family vacation.”

But we’ll let Ed explain further:

... the SNAFUs in this book are not your run-of-the-mill slip-ups, like accidentally using ranch dressing as coffee creamer (in my defense, it was in a very tiny, fancy-looking carafe). No, these are the big mamas—the epic blunders that unravel like slow-motion train wrecks, except it’s like ten different trains derailing in every direction, with clueless officials insisting, “Everything’s fine!” while entire towns get leveled in the chaos.

These disasters aren’t confined to one poor soul making a bad decision—they’re massive, institution-shaking calamities that drag entire governments, corporations, and far too many innocent bystanders along for the ride. And yet, like rubberneckers at a car crash, we just have to watch. There’s something weirdly irresistible—almost primal—about witnessing a colossal screwup.

That’s why he started the SNAFU podcast—and eventually wrote SNAFU the book. The stories span decades and disasters, painting a portrait of American dysfunction that somehow leaves you feeling better about your own life choices.

You’ve probably heard the old saying that tragedy plus time equals comedy. Mark Twain supposedly said that (or was it Carol Burnett? Either way, I’m stealing it). And that’s certainly true, but I would argue this book is about much more than retroactive comedy—it’s also about reassurance. Because if history teaches us anything, it’s that we’ve been royally screwing things up for centuries, and yet, somehow, we’re still here…

We are living in a time of nonstop anxiety…Climate change, global conflict, social upheaval—sometimes it feels like the whole planet is just one bad decision away from getting snuffed out like a birthday candle in a tornado. But guess what? That feeling isn’t new. People in the 1950s were terrified of nuclear annihilation. The 1970s brought an energy crisis and disco. The 1980s had acid-washed jeans and actual acid rain. And somehow, despite all of it, life moved forward. Humanity stumbled, adapted, and—against all odds—kept going.

That’s the strangely uplifting message buried in all these SNAFUs. No matter how idiotic, shortsighted, heartbreaking, or downright absurd our mistakes have been, they haven’t taken us out yet. And it turns out studying them can be a weirdly optimistic exercise. Sure, it’s easy to despair when the world feels like it’s unraveling, but looking back at our collective blunders serves as a powerful reminder: We’ve been here before, and we’ll get through this, too.

At Soul Boom, we believe this moment in history is something more than a mess—it’s a turning point. A liminal chapter. We’re more connected than ever, but still using outdated maps. We haven’t yet figured out how to live as a planetary civilization. And we’re feeling the effects of that gap.

But the longing for unity, justice, and transformation? It’s real. It’s rising. And it calls for one thing above all: a shared commitment to the common good.

This is our adolescence. Let’s grow into our collective adulthood—with compassion, with accountability, and yes—with humor.

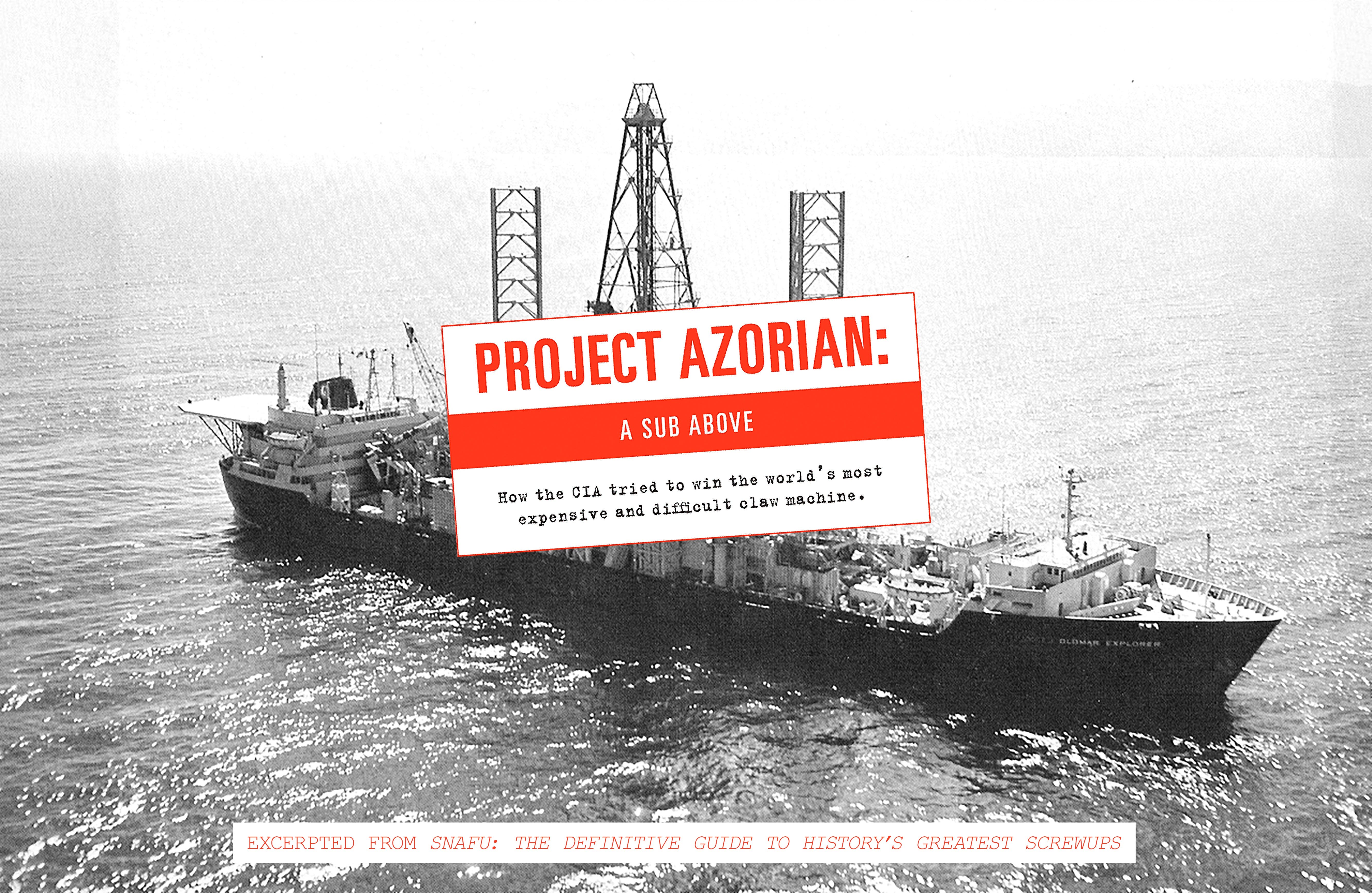

We’re including a wild excerpt from Ed’s book about a CIA plot to build the world’s most expensive underwater claw machine. It’s funny, shocking, historically rich, and oddly hopeful.

Here’s to the good old days—past, present, and still to come,

The Soul Boom Team

by Ed Helms

In the early hours of June 5, 1974, security guard Mike Davis stood outside the building at 7020 Romaine Street in Hollywood. As he enjoyed the balmy sixty-degree weather, the light of the full moon shining through the cloudy sky, Mike suddenly felt something pressing into his back.

A gun.

A group of four burglars grabbed poor Mike and forced him to unlock the door. Why did these thieves want to get inside so badly? Because the building Mike was guarding was the corporate headquarters of Howard Hughes, the reclusive billionaire aviator, film producer, philanthropist, and all-around all-American weirdo rich guy. Think Jeff Bezos, but with a pencil-thin mustache and actually, ya know, adventurous.

After the burglars forced Mike to let them in, they wheeled in a heavy tank filled with highly flammable acetylene gas. They mazed their way through the Art Deco–style, two-story building before finally marching into an office that contained a safe and a large vault. Jackpot.

Wait a second, you might be asking, the burglars just waltzed right in there? Shouldn’t this famously secretive guy have some sort of security or alarm system for this building that houses his sensitive, top secret shit?

Well, reader, there was an alarm system. It just wasn’t working. Actually, it had been out of order for some time. And Mike was the only guard on duty. Seriously, this place had worse security than the gas station where my friends and I used to steal packs of gum as kids.

The burglars turned on the acetylene tank and grabbed their torches. You know the big heist scene in Thief where James Caan puts on a welding suit, lights a long-ass torch, and drives it straight into a locked metal door as sparks fly everywhere? Just imagine that. And after hours of slowly melting the door off its hinges, one of the burglars took off his suit, wiped his brow, and smirked as he said: “We’re in.”

The burglars stormed into the vault and grabbed everything they could. Four hours after first arriving, the burglars escaped, hauling the acetylene tank with them and all their stolen loot. They ended up with quite the grab bag: $68,000 in cash, two Wedgwood vases, a ceramic samovar, two butterfly collections, three digital watches, and an antique Mongolian eating bowl. Again, Hughes was a rich weirdo. Maybe he was planning on sitting down to a delicious meal of pickled butterflies, perfectly arranged in his Mongolian bowl.

But even more valuable than those preserved critters and antiques were two footlockers full of files—documents that would soon cause an international diplomatic scandal. These documents revealed Hughes’s participation in a secret CIA plot that involved a sunken Soviet submarine, underwater nukes, and the most difficult claw game in the world.

It all began six years earlier on March 1, 1968, when a Soviet submarine named K-129 sailed out from a naval base in Petropavlovsk, way out in the Russian Far East and over 4,000 miles from Moscow. K-129 was equipped with three nuclear warheads; each single warhead was nearly seventy times more powerful than the bomb dropped by the United States on Hiroshima. In the case of nuclear war, the sub would fire off its nukes to targets on the West Coast of the United States.

The sub began its standard peacetime patrol in the North Pacific. But at some point in the middle of March, the Soviets lost communication with K-129. The sub went radio silent. We still don’t know exactly what happened.

A declassified, heavily redacted CIA report published in 1985 simply says that “the submarine suffered an accident—cause unknown—and sank 1,560 miles northwest of Hawai’i.” The report is also mum about how the CIA came to ascertain the location of the sub’s sinking. According to military historian Matthew Aid, archival documents have suggested that the US Navy’s underwater sonar, the Sound Surveillance System, might have discovered the location of the sunken sub.

Whatever the case, the Soviets had lost a nuke-equipped submarine. They fruitlessly searched for it for two months, then gave up. And that whole time, the CIA knew exactly where it was.

Why was the CIA so interested in the sub? Because inside was potentially valuable intelligence that could reveal the inner workings of the Soviet Navy: codebooks, decoding machines, and burst transmitters—not to mention the nukes themselves, which would still be functional.

There was just one problem. K-129 lay 16,500 feet beneath the surface of the ocean. How the hell do you get down there in the first place? And once you’re three miles deep, how do you then bring the sub back up to the surface? These questions might have left a recovery effort dead in the water, but with such a tantalizing prize on the ocean floor, the CIA couldn’t resist.

To consider their options, longtime CIA agent John Parangosky convened a task force in an anonymous office near, of all places, Tysons Corner, the largest shopping mall in the DC area. Today if you showed up there for a meeting, you could browse the racks at Urban Outfitters and grab a pretzel from Auntie Anne’s, but there isn’t a secret meeting room anymore. At least Parangosky got in ahead of Auntie Anne, though. According to the book The Taking of K-129, he “was a fair boss, occasionally even friendly, but no one was immune from his temper.” I assume Parangosky wasn’t very forgiving if you came back late from lunch at the food court.

Anyway, Parangosky assembled a team of scientists, engineers, and submarine experts to brainstorm ideas for the sub rescue mission. Imagine a bunch of suits scribbling ideas on a whiteboard. Maybe they could place “buoyant material” (kind of like a really sophisticated pool noodle) under the sub, and then hope the material was floaty enough to carry the sub all the way up. Maybe instead of a pool noodle, they could simply generate a buoyant gas like hydrogen or nitrogen through electrolysis, causing the sub to float back up without even touching it.

All of these ideas were 100 percent real and actually considered by the CIA. And yeah, if they sounded harebrained and doomed to fail, you’d be right. But believe it or not, the solution Parangosky and company finally landed on was even more harebrained: the doomedest to fail of them all.

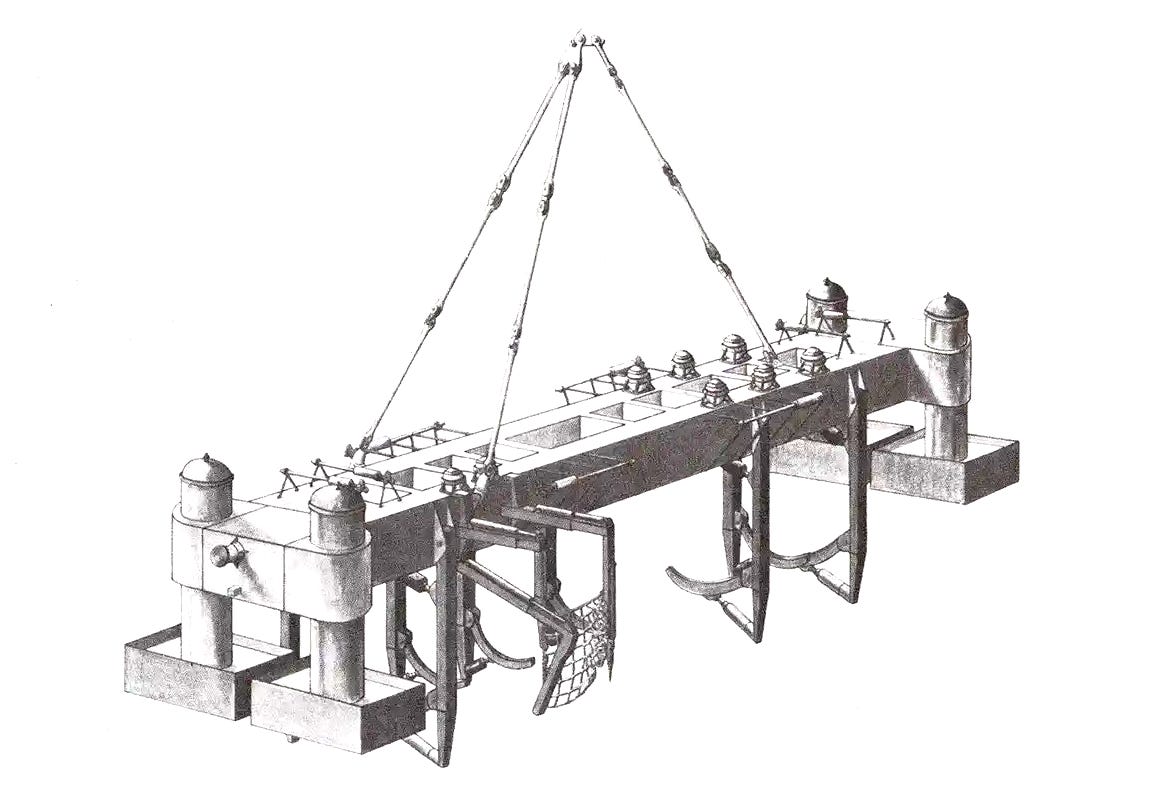

That’s right, folks. Parangosky and Co. decided to use a literal claw to pick up K-129 from the bottom of the ocean and lift it back up through brute force.

The claw would consist of five separate grasping claws, connected to heavy-duty winches that would be mounted onto a specially built ship. The ship had to be able to withstand the weight of the 1,750-ton Soviet sub. The plan was for the claw to descend to the seafloor, slip a sort of metal hammock beneath the sub, and then gingerly lift it back up.

You’re probably picturing one of those arcade claw games at Chuck E. Cheese right now. And yeah, that’s exactly what I want you to imagine. Because think about how hard it is to even pick up a stuffed animal from the bottom of the machine. Those things are impossible to win! Now think about trying to pick up a submarine that’s more than three miles underwater and has the weight of about 875 passenger cars. What could possibly go wrong?

As it turns out, just about everything. And they knew it, too. Senior intelligence officers gave the project a 10 percent success rate. If you were a civil engineer and designed a bridge that had a 90 percent chance of collapsing, what do you think your boss would say? Would they be like, “Great idea! Here’s an ungodly amount of money to build this bridge that, nine times out of ten, will catastrophically fail!”?

Well, that’s exactly what the CIA decided to do. On October 30, 1970, two years after K-129 sank, the agency authorized Project Azorian, the official name for the mission to recover the Soviet sub.

There were definitely concerns about the mission, especially the constantly ballooning cost. Suspiciously, the declassified CIA report redacts any and all specific dollar figures. What it does mention is how, like the making of Apocalypse Now, the project kept getting delayed and going over budget. For example, Project Azorian “was first costed at [REDACTED] in 1970. In less than a year it had jumped more than 50 percent to some [REDACTED].”

We’ll probably never know the exact cost, but Matthew Aid estimates it at half a billion with a b dollars at the time. That’s over $3 billion in today’s money. How much is $3 billion? It’s more than the individual GDP of thirty-five sovereign nations. In other words, this CIA floating claw machine was more expensive than entire economies. Which, damn, that makes paying a quarter to play a claw game at Chuck E. Cheese seem like a bargain.

The CIA had one last problem with Project Azorian: How do we keep this thing a secret? We can’t exactly tell everyone we’re building a giant claw ship to retrieve a Soviet nuclear submarine. By 1971, the United States and the USSR were in a period of détente—the two countries had signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty in 1968—and a mission to essentially steal a Soviet sub wouldn’t be great for diplomatic relations.

So the CIA needed a cover story and decided to reach out to Howard Hughes. Could Hughes pretend to be constructing a research vessel equipped with a giant claw for the purpose of mining deep-sea metals? Hughes was in many ways a perfect choice: He already had a reputation as a secretive, eccentric billionaire who invested in all sorts of expensive projects, and already had a stated interest in deep-sea mining. He had also previously collaborated with the government to develop satellites for classified intelligence purposes.

And sure enough, Hughes was more than happy to help. Construction on the Hughes Glomar Explorer—Hughes also agreed to let the claw ship be named after him—began in 1971 in a shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania, a half hour south of Philadelphia. In November 1972, the ship was christened in the usual way—smashing a bottle of champagne on the hull. Not that things exactly went to plan. The person who was supposed to smash the bottle missed twice, and had to throw a third bottle at the ship as it cast off. Not everything is an omen, but...sometimes such occurrences are a little on the nose.

The CIA was able to maintain this cover for quite some time. When the HGE (let’s call it the HGE so I don’t have to keep saying “Glomar”) finally set sail in 1973, the Los Angeles Times noted, “Newsmen were not permitted to view the launch, and details of the ship’s destination and mission were not released.” The press chalked up the secrecy surrounding the ship and its mission to Hughes’s own propensity for privacy.

The HGE first sailed from Pennsylvania to Bermuda. Because it was too big to pass through the Panama Canal, it had to sail all the way around the southern tip of South America.

After making a brief pit stop in Chile, the HGE sailed on and reached its destination of Long Beach, California, at the end of September, where it stayed at harbor for several months in preparation for the recovery mission. It also kept experiencing mechanical failures. Literal cracks started showing in the hull, which divers had to seal up. This thing was pretty much held together by duct tape and a prayer. The crew couldn’t fix everything and eventually just gave up: “One small but persistent seal leak was never corrected, and the seepage of a few gallons per hour was accepted. Thus, the HGE lived with a small puddle in the starboard wing well.”

Kind of embarrassing. Imagine a real estate agent trying to sell you a house and explaining that there’s a permanent puddle on the top floor because the roof isn’t fully sealed.

But! The CIA had already invested too much time and too many resources into this over-budget, creaky-ass claw ship. I guess you could say that they’d fallen into the (sorry) sunk cost fallacy (so sorry). On June 7, 1974, President Nixon personally gave the official and final green light to recover the sub.

It was showtime.

On Independence Day, as fireworks exploded over cities across the country in celebration of America’s 198th birthday, the HGE traveled to a spot 1,560 miles northeast of Hawai’i, where K-129 lay at the bottom of the ocean. John Parangosky, the CIA agent who had come up with the whole claw idea, was closely monitoring the mission back at headquarters.

But when the HGE arrived at the site, the mission was very nearly thwarted. The crew noticed Soviet helicopters flying overhead, taking photos. Plus, Soviet Navy ships kept surveilling the HGE. One vessel named Chazhma came within a mile of the HGE and sent a radio transmission: “What are you doing here?”

The Americans replied, “We are conducting ocean mining tests—deep ocean mining tests.”

After a few more tense back-and-forths, Chazhma signed off with, “I wish you all the best,” and went on its merry way to Petropavlovsk—the port city that K-129 originally set out from. The Soviets were none the wiser about the HGE’s true purpose.

But even with the Soviets off their backs, the crew still had to worry about maintenance issues, which just kept getting worse. One mechanical failure caused “a display of noise, fire (sparks and smoke primarily) and spastic shaking of the derrick.” And as I always say: Whenever there’s spastic shaking of the derrick, things aren’t looking good. The crew in general weren’t confident about their chances for success. In fact, they had nicknamed the claw “Clementine,” since they figured the sub was “lost and gone forever.”

But it was too late to back out now. Just after midnight on July 21, the world’s most expensive and difficult claw game began. The ship’s onboard computers flashed with real-time info and photos as the massive winch slowly unspooled miles and miles of piping, with Clementine descending into the deepest reaches of the Pacific. According to the book Blind Man’s Bluff, one man who recruited sailors for the crew later compared the mission to “lifting a 25-foot-long steel tube off the ground with a cable lowered from the top of the 110-story World Trade Center, on a pitch-black night haunted by swirling winds.” So, you know, everyone was set up for success.

Down Clementine went. Not much lives 16,500 feet beneath the surface of the ocean. That depth is considered the “abyssal zone,” where there’s no sunlight and the temperature is just above freezing. The water pressure can reach up to 600 times the pressure of the atmosphere. The only things swimming around are freaky-looking sea creatures with creepy names like “faceless fish” and “fangtooths.”

It took eleven days for Clementine to reach the bottom of the ocean. Using the built-in cameras, the crew carefully maneuvered the claw to grasp the sub...only for them to miscalculate and slam the claw into the seabed. Whoops. But Clementine, faithful ol’ girl, was still intact. They went in for another attempt, and this time were right on target. Clementine latched on to the sub and gingerly began lifting it up, at an agonizingly slow rate of six feet per minute. It took another eight days for the claw to rise from the crash site. Imagine the crew’s excitement when, after waiting for more than a week, the claw finally returned to the surface. To quote another American military vessel: Mission accomplished!

And then imagine their disappointment when the claw emerged...with only a thirty-eight-foot-long section of the front hull. About two-thirds of the sub had broken off. On Clementine’s way up, three of the five grasping claws had cracked and sunk. With only two claws still holding the highly fragile sub, the sub then split off and sank as well, along with the nuclear missile, codebooks, decoding machines, and the burst transmitters. Essentially, they lost everything the CIA was dying to reclaim.

What the claw did recover were the bodies of six of the sub’s crew members who were trapped in the front 10 percent of the sub. Parangosky had ordered that any recovered bodies would be given a proper funeral. The Soviet crew members were buried at sea with full military honors; the funeral was filmed, and the recording was given to the Russian government a year after the Soviet Union’s collapse. There’s honestly something touching about that—the crew of K-129 may have been working for America’s sworn enemy, but they certainly didn’t deserve to die in the depths of the Pacific, thousands of miles from home. At least after their deaths, they were treated with a little humanity.

And so it was that on August 8, 1974, with most of K-129 still at the bottom of the ocean, the Hughes Glomar Explorer began its voyage home.

Well, the CIA told itself, at least we were able to maintain our cover story and no one’s the wiser that our mission failed. Some in the government even believed Project Azorian to be a success—in a post-mission White House meeting, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger declared that “the operation is a marvel.” The CIA figured that even if they didn’t recover the entire sub, they’d proved that it was at least possible. John Parangosky pushed for a second attempt, which was scheduled for July 1975. Hopefully they could keep the nosy press from catching on one more time.

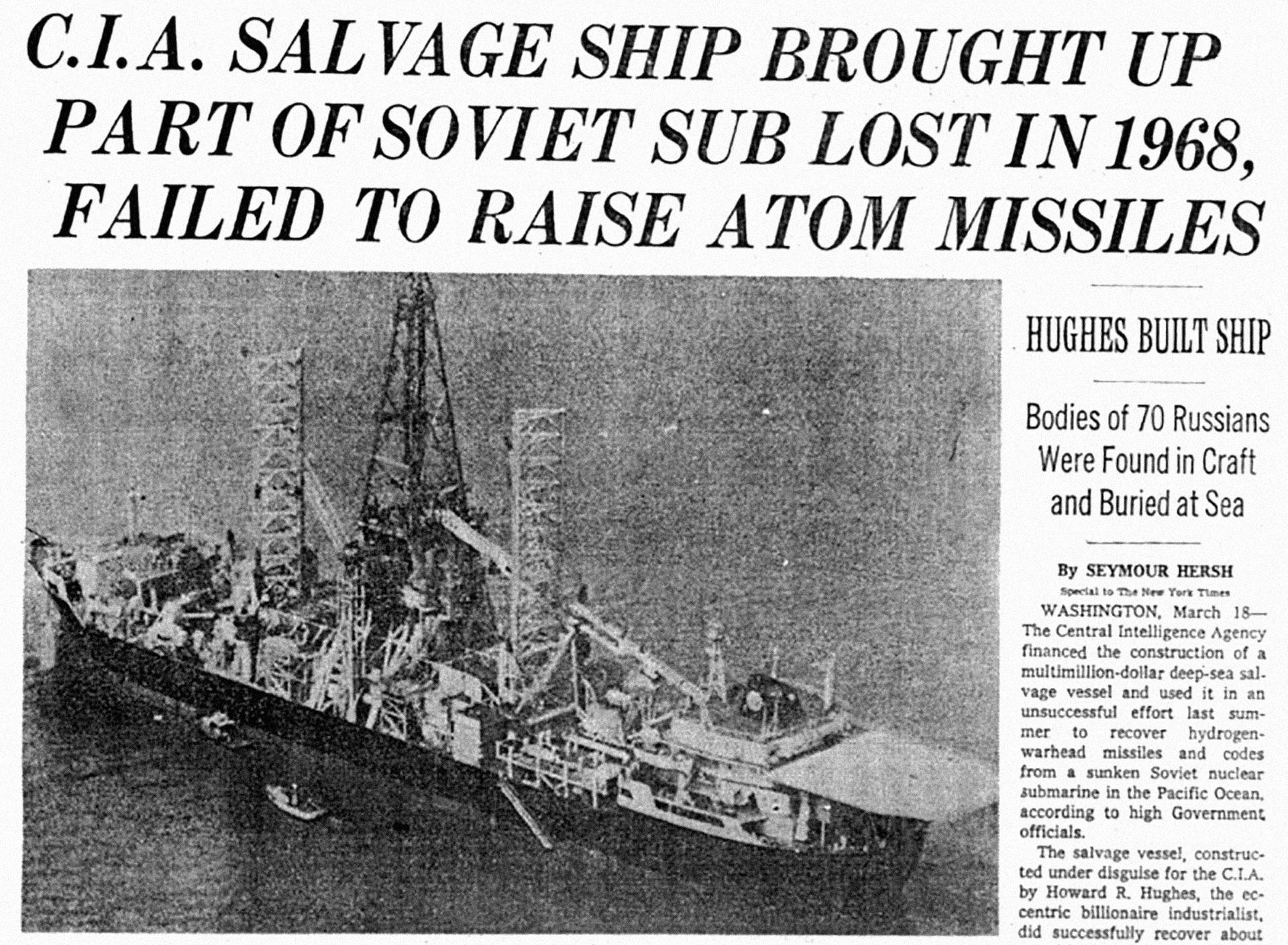

But alas, back on June 5, 1974—while the HGE was docked thirty-three miles south in Long Beach waiting to launch out into the Pacific—a group of four burglars broke into the Hughes corporate headquarters and stole top secret documents that revealed the true purpose of the ship. The press discovered these documents, and Azorian’s cover story was finally blown in February 1975, when the Los Angeles Times published the first article revealing the actual mission of the HGE. The following month, our good ol’ pal, Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist Jack Anderson—you’ll remember him from Operation Popeye—broke the story of Azorian on national TV.

And—surprise, surprise—our other legendary journalist Seymour Hersh also wrote about the failed mission for the New York Times. (Anyone else miss the glory days of gumshoe reporters like Anderson and Hersch?) Hersh spoke to an anonymous navy admiral who pointed out that even if the CIA did recover the secret Soviet codebooks (which would’ve been seven years out of date by that point), the codes wouldn’t mean much because they were automatically, randomly scrambled every twenty-four hours.

By June 1975, all this bad press forced the CIA to cancel the planned second recovery attempt. John Parangosky, the agent who had spearheaded Project Azorian, had retired by then. And naturally, the Soviets weren’t happy about the news, either. The USSR ambassador to the United States pressed for more details about Project Azorian—perhaps the Soviets were embarrassed that despite heavily surveilling the HGE, they’d failed to ascertain its true purpose.

American journalists also kept digging. A journalist named Harriet Ann Phillippi filed a Freedom of Information Act request for more info. Walking a diplomatic tightrope, the CIA stated that they could “neither confirm nor deny” the agency’s connection to the Hughes Glomar Explorer’s true mission. It’s the perfect non-denial denial: Maybe this thing isn’t true. But if it is true, we can’t tell you about it! A court case the following year upheld the CIA’s “refusal to confirm or deny existence of records,” and Phillippi’s FOIA request was thrown out.

You’ve probably heard this phrase, of course. It became so widespread and infamous that today it’s known as the “Glomar response.” In perhaps the worst example of branded accounts on Twitter (now X), @CIA’s first ever tweet in 2014 was, “We can neither confirm nor deny that this is our first tweet.”

Hilarious.

As for the Hughes Glomar Explorer itself, in 1976 the US government tried to auction it off to the public. The maximum offer they received was $2 million, which was nothing compared to the estimated total mission cost of $500 million (again, the actual mission cost is still classified info). The HGE was put into storage, and over the decades was leased to various private interests to drill for oil and to actually mine for deep-sea metals, before finally being completely scrapped in 2015—all 51,000 tons of it.

In an ironic twist, there’s probably more of K-129 left than the massive claw machine that was built to recover it. Maybe James Cameron can build another deep-sea explorer and try to recover the sunken Soviet submarine himself—but on the other hand, perhaps it’s best to let sleeping subs lie.

Excerpted from SNAFU: The Definitive Guide to History’s Greatest Screwups Copyright © 2025 Ed Helms. Published by Grand Central Publishing, a Hachette Book Group company. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Ed Helms is a comedian, actor, writer, and banjo enthusiast best known for his roles as Andy Bernard on The Office, Stu in The Hangover trilogy, and as a correspondent on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. A graduate of Oberlin College with a degree in film theory and technology, Ed began his career in New York’s comedy scene before rising to national prominence through sharp political satire and absurdist character work. Behind his signature wide grin lies a curious, reflective thinker with a deep love for American history, music, and culture. He is the creator and host of the podcast SNAFU, which explores the funniest, weirdest, and most catastrophic screwups in U.S. history—blending rigorous research with sharp humor. Ed is also the author of SNAFU: The Book, a wild, oddly hopeful romp through history’s most jaw-dropping fiascos. He lives in Los Angeles, where he balances creative projects with parenting, bluegrass jamming, and finding the line between foolishness and wisdom.

Fantastic article! Thank you! 😊

Will listen to their podcast later.

WOW! Thanks for this! Tomorrow is my birthday, and this feels like an early gift: two of my favorite actors just being themselves! I can't wait to view this podcast!