Dr. Mustafa Santiago Ali on our Toxic Politics

“I Couldn’t Be Part of Hurting the People I Promised to Uplift”

Greetings to all you tree huggers and lovers of breathable air 🌎

On this week’s episode of the Soul Boom podcast, Rainn sits down with Dr. Mustafa Santiago Ali — environmental justice leader, poet, former senior official at the Environmental Protection Agency, longtime community advocate, and a man whose life bridges rural Appalachia and the federal government.

His résumé is formidable. But what becomes clear in conversation is that he does not see himself as the story. He is part of a story.

And it’s a part of a story that feels especially resonant during Black History Month. Black History Month often highlights individual trailblazers — and rightly so. But what Dr. Ali makes unmistakably clear that justice is not the achievement of a single charismatic figure. It is the product of a movement built by frontline communities who refused to accept that their neighborhoods were disposable.

And when we think of justice, we might think of abolition, civil rights marches, voting rights, desegregation, the ongoing struggle for equity and dignity. We understand that arc. It is foundational to the American story. What we talk about far less is the pursuit of environmental justice. And yet, it has always been part of that broader struggle.

Mustaga names the elders to it. Hazel Johnson, often called the mother of the environmental justice movement, organizing on Chicago’s South Side long before environmental justice was a recognized field. Dr. Robert Bullard, documenting through scholarship what communities were already experiencing. Bunyan Bryant. Richard Moore. Tom Goldtooth. These pioneers, all people of color, insisted that clean air and safe water were not luxuries.

The Office of Environmental Justice at the EPA did not emerge because policy wonks had a brainstorm. It was created because Black communities demanded protection from disproportionate harm.

Dr. Ali grew up in a tiny town in West Virginia — fewer than 500 people, one stop sign, a whole lot of love. His grandfather, a coal miner and farmer, hosted porch conversations about workers’ rights and civil rights. His mother practiced radical hospitality, raising far more children than her own four and ensuring no one in the community went hungry.

It sounds idyllic. And in many ways, it was. But there was also a coal-fired power plant across the river. Emissions drifting over homes. A cancer cluster. Miners coming out of shafts with black lung. The kind of damage that rarely commands national headlines but shapes lives all the same.

Long before there was language like “environmental equity,” there was lived reality.

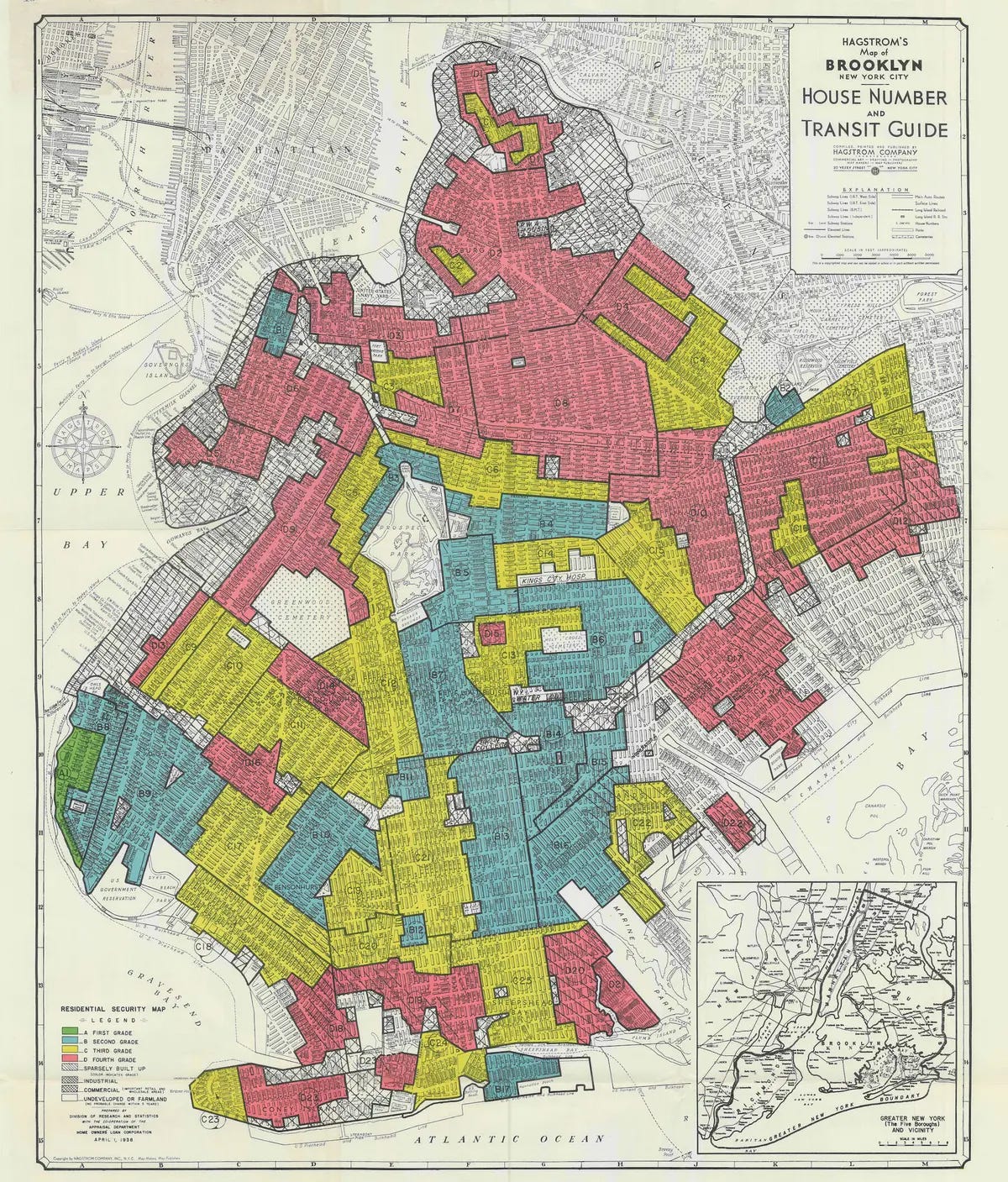

And that reality has followed familiar patterns across the country. Redlining and restrictive covenants did more than determine who could live where. They determined which communities would be adjacent to highways, refineries, landfills, and chemical facilities. Over time, pollution accumulates. Health burdens accumulate. Wealth gaps widen. Generations inherit the consequences.

When we reflect on Black History Month, we often recall dramatic turning points. What environmental justice reveals is the slower grind — the asthma rates, the contaminated water systems, the shortened life expectancy. It is less visible. It is no less urgent.

As we face what scientists describe as three interconnected environmental catastrophes — pervasive pollution, accelerating mass extinction, and climate collapse — it becomes harder to treat environmental justice as a peripheral issue. These crises are intertwined, and their impacts land hardest on communities with the fewest resources.

This is not incidental.

Dr. Ali has worked inside federal agencies, advised administrations, and seen the machinery of government up close. He understands the necessity of policy. He also understands its limits.

He speaks about “ground truth.” Policy developed in theory must meet lived experience. Real change happens when communities are not treated as passive recipients of solutions but as partners — even drivers — of them.

He shares the story of the Regenesis Project in Spartanburg, South Carolina. What began as a modest federal grant eventually leveraged hundreds of millions of dollars in investment. Safer infrastructure. Green housing that dramatically lowered utility bills. Workforce training that equipped residents with skills for clean energy jobs. Community spaces designed for connection.

It required persistence, partnership, and a long horizon. That long horizon feels deeply aligned with the Black freedom tradition — the understanding that change is cumulative. It builds. It stretches across generations.

Dr. Ali describes the environmental crisis as fundamentally a spiritual one and affirms that environmental justice begins with honoring the sacred interconnectedness of all life. Soil microbes, rivers, wildlife, human communities — none exist in isolation. When we operate from an extraction mindset — take, burn, discard — we are expressing a worldview of separation. We are forgetting that what harms the web ultimately harms us.

Black communities have long cultivated spiritual traditions rooted in interdependence and resilience. The Black church, ancestral memory, radical care for neighbors — these are not incidental cultural artifacts. They are frameworks for survival and moral clarity.

Environmental justice, in that sense, is not merely regulatory reform. It is relational repair.

Dr. Ali eventually resigned from the EPA when he believed he could no longer fulfill his oath under shifting political priorities. His resignation letter reached more than a million readers. It surprised him. Environmental justice had rarely commanded that level of attention.

But the response signaled something important: people intuitively understand that what is at stake is not abstract. It is bodily. It is communal. It is generational. Environmental justice is not a niche issue tucked into climate policy debates. It is about whether certain communities are treated as sacrifice zones. It is about whether every child deserves clean air, safe water, and a future not quietly compromised by toxins.

It is essential to center those most in harm’s way. But it is also essential to recognize that none of us are outside this story. We are often indifferent to suffering when it does not appear to be ours. If it is happening elsewhere — to someone else — it might feel like it’s not so big a deal.

From the Soul Boom perspective, this lack of empathy — or even awareness — reflects a culture living in the illusion of separation. Denying our interdependence despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary feels convenient. Until it isn’t.

Many of us know the famous quote from Martin Niemöller:

“First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Environmental collapse unfolds differently. It is not a regime. But the illusion of separation is similar.

Is this perhaps the story we see unfolding:

First the seas rose around island nations, and I did not speak out—because I did not live on an island.

Then drought gripped farmers in East Africa, and I did not speak out—because I was not a farmer.

Then wildfires tore through Indigenous lands and the Amazon burned, and I did not speak out—because it was not my forest.

Then toxic water flowed through pipes in communities like Flint and Jackson, and I did not speak out—because it was not my tap.

Then the smoke filled my own skies, the insurance company left my state, the heat wave took someone I loved—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Environmental justice asks us to let go of the comforting fiction that harm can be contained. What we ignore in one place eventually reshapes every place.

The elders Dr. Ali honors understood that no community is expendable. That insight may be one of the most necessary moral guides for the spiritual revolution we’re here to spark.

Wow. Very eloquent, very respectful, and very insightful. I admit that I didn't know much about environmental justice; But Dr. Ali has given us a terrific overview, and an excellent example in the work being done in Spartanburg. As a relatively new South Carolinian, this makes me proud, and I hope that Spartanburg's initiatives can shine a light on the rest of our state. Thank you!