Exclusive excerpt: Adam Grant on Our Hidden Potential

Plus: Adam joins Rainn for an illuminating episode of Soul Boom

Greetings to All You Glorious Uncut Gems!

This week on the Soul Boom podcast, Rainn sits down with organizational psychologist and bestselling author Adam Grant to talk about what it really takes to leap into the unknown—and why confidence often follows action, not the other way around.

From springboard diving mishaps to the patterns that can trap us in failure, Adam shares insights on resilience, learning from setbacks, and living by your values. It’s a conversation that’s equal parts playful and profound, and might just give you the nudge you need to take your own next leap.

The twin invocations of hidden potential and diamonds in the rough invoked in Adam’s latest work brought to mind the words of Bahá’u’lláh, the 19th century founder of the Bahá’í Faith:

“Man is the supreme Talisman. Lack of a proper education hath, however, deprived him of that which he doth inherently possess. …

Regard man as a mine rich in gems of inestimable value. Education can, alone, cause it to reveal its treasures, and enable mankind to benefit therefrom.”

In Bahá’u’lláh’s milieu, people often saw talismans as objects with supernatural powers—much as some today might think of crystals or charms. His message was radical: the true talisman, the real seat of transformative power, is the human being. And with the metaphor of a mine rich in gems, the point is pushed further—our value is inherent, but it takes the right tools, guidance, and conditions to bring those treasures to light.

The word education can conjure a narrow picture—children in a classroom—but culture itself is the ever-present educator of all of us. And in modern life, the media we consume is arguably the most dominant force in that process. That’s why the Soul Boom team is so passionate about our work.

But we’re not naive: we know the influence of early life, especially childhood, is uniquely powerful—and that’s why the insights of Adam Grant and his cohort are so vital. Adam’s framing is the research-grounded counterpart to what we might think of as a spiritual truth: full potential is not visible at the start; it emerges when people are given opportunity, support, and the tools to grow.

In his book, Hidden Potential, Adam Grant lays out a three-part roadmap for unlocking human possibility. First, he explores the character skills—like discipline, determination, and collaboration—that catapult us to greater heights. Second, he shows how to build the kind of scaffolding that keeps motivation humming without burning us out—proof that growth doesn’t have to come at the cost of exhaustion. Finally, he tackles how to redesign systems so opportunity flows to those too often overlooked, turning potential into real progress for everyone. It’s a brilliant framework—and we think it’s a book many of you would thoroughly dog-ear and underline.

That’s why we’re sharing a passage from it in this edition of the Dispatch.

May it inspire every one of us to see the untapped worth in ourselves and each other—and may we all support one another in bringing it forth.

After all, if we can’t do that much, it’s not really a spiritual revolution, now is it?The Soul Boom Team

Excerpt from Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things

by Adam Grant

Note: This excerpt has been lightly edited for length.

Growing Roses from Concrete

"Did you hear about the rose that grew from a crack in the concrete

Proving nature's law is wrong it learned 2 walk without having feet

Funny it seems but by keeping its dreams it learned 2 breathe fresh air"

– Tupac Shakur

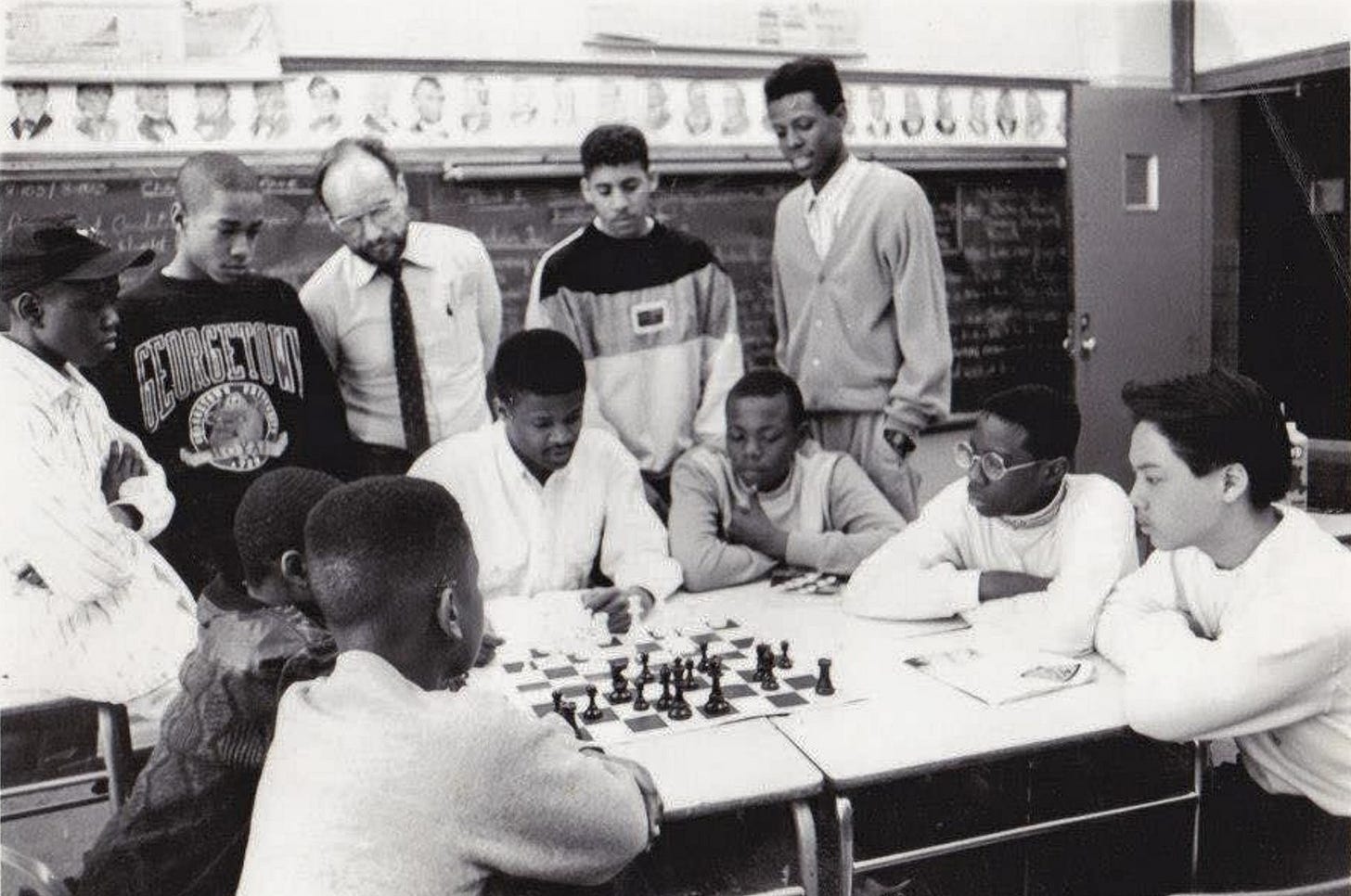

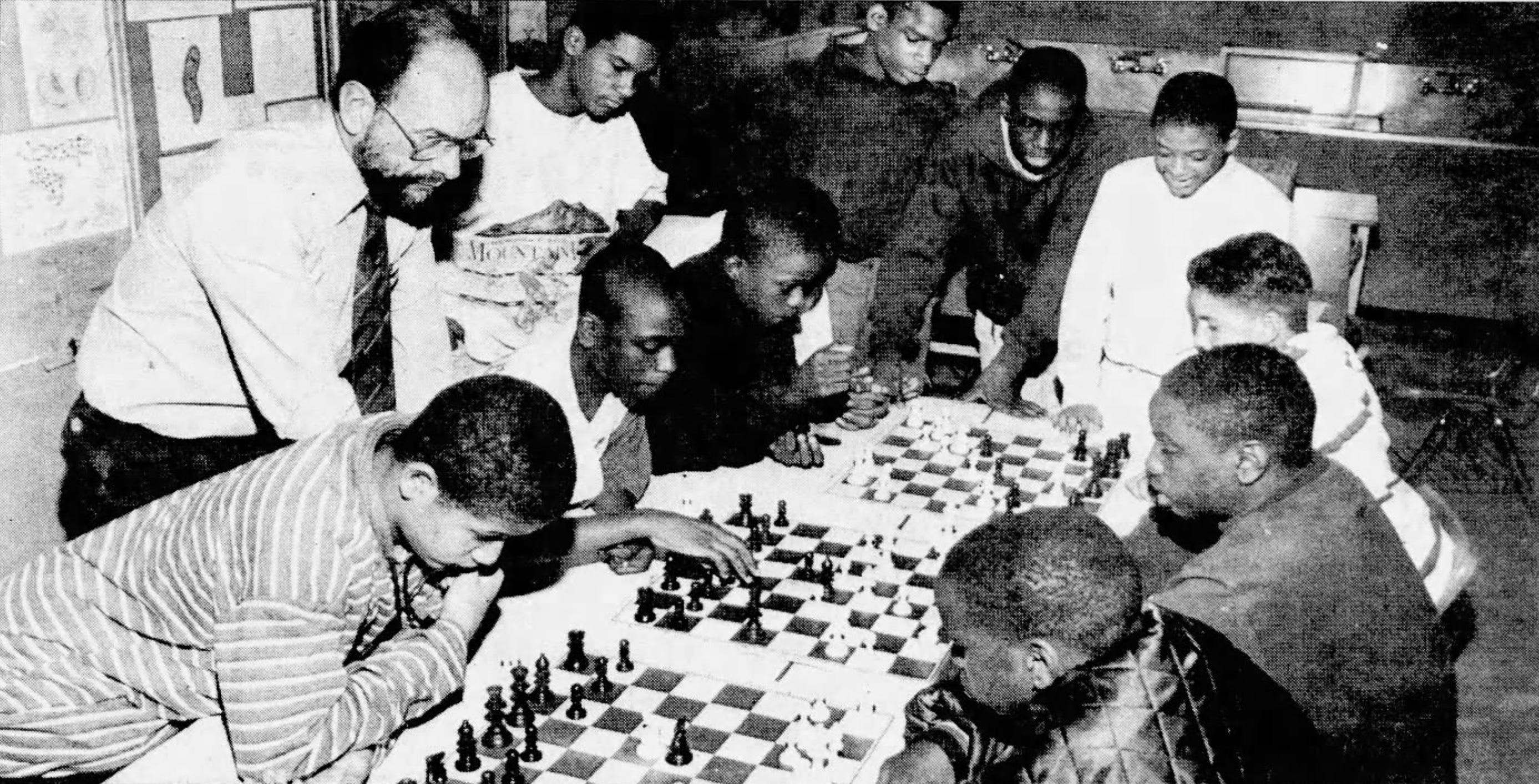

On a chilly spring weekend in 1991, some of America’s sharpest young minds gathered in a hotel outside Detroit. The hall buzzed with chatter as students worked their way to their assigned seats. The moment the clocks started, the room fell silent. The only sound was click, click, click. All eyes were locked on rows of black-and-white squares. It was the National Junior High Chess Championships.

In recent years, the tournament had been dominated by teams from fancy private schools and magnet schools. They had the resources to make chess part of the school curriculum. The defending champion was Dalton, an elite prep school in New York City that had won three straight national titles.

Dalton had built the chess equivalent of an Olympic training center. Each kindergartner took a semester of chess, and every first grader studied the game for a full year. The most talented students qualified for lessons before and after school with one of the country’s best chess teachers. Dalton’s crown jewel was child prodigy Josh Waitzkin, whose life story would become the basis for the hit movie Searching for Bobby Fischer just two years later. Even though Josh and another star player weren’t competing this year, Dalton had a formidable team.

No one saw the Raging Rooks as contenders. As they walked nervously into the hotel, heads turned. They had very little in common with their wealthy white opponents. The Raging Rooks were a group of poor students of color—six Black boys, one Latino, one Asian American. They lived in neighborhoods ravaged by drugs, violence, and crime. Most of them grew up in single-parent homes, raised by mothers, aunts, or grandmothers with incomes less than the cost of Dalton tuition.

The Raging Rooks were eighth- and ninth-graders hailing from JHS 43, a public middle school in Harlem. Unlike their adversaries at Dalton, they didn’t have a decade of training or years of competition under their belts. Some of them had only learned the game in sixth grade. The team captain, Kasaun Henry, had picked up chess at age twelve and practiced in a park with a drug dealer.

At nationals, teams got to keep their highest scores and throw out the rest. Teams as large as Dalton’s could drop as many as six scores. But the Raging Rooks barely fielded enough players to compete. Every score would count—they had no insurance policy. To have any shot at success, they would all have to perform at their peak.

The Raging Rooks started strong. Early on, their weakest player upset an opponent ranked hundreds of points above him. The rest of the team rose to the occasion, checkmating foes who were far more seasoned. Going into the semifinals, of 63 teams competing, the Raging Rooks were in third place.

Despite their inexperience, they had a secret weapon. Their coach was a young chess master named Maurice Ashley. A Jamaican immigrant in his mid-twenties, Maurice was on a mission to shatter the stereotype that darker-skinned kids weren’t bright. He knew from experience that although talent is evenly distributed, opportunity is not. He could see potential where others had missed it. He was looking to grow roses in concrete.

But in the penultimate round of nationals, Maurice watched his team begin to slip. After gaining a lead, Kasaun blundered and barely squeaked out a draw. Another player was on the brink of victory when his opponent managed to capture his queen and beat him. He broke down in tears and bolted out of the room. One game got off to such an ugly start that Maurice walked out of the playing hall altogether. It was too painful to watch. By the end of the round, the Raging Rooks had fallen from third to fifth place.

Maurice reminded them they could control only their decisions—not their results. To catch up, the Raging Rooks would have to win their four final games and pray for the top teams to lose theirs. But regardless of what happened, they were now among the best in the country. They didn’t have to win the tournament to win people’s hearts. They had already smashed all expectations.

Chess is known as a game of genius. The top young players tend to be whiz kids with the raw brainpower to memorize sequences, rapidly analyze scenarios, and see many steps ahead. If you want to build a championship chess team, your best bet is to do what Dalton did: recruit a bunch of child prodigies and put them through intensive training from an early age.

Maurice did the opposite: he started coaching a group of middle schoolers who happened to be interested and available. One was the class bully. They were mostly B students, and they weren’t selected for any special chess aptitude. “We didn’t have any stars on our team,” Maurice recalls.

Yet as the final round played out, the Raging Rooks managed to hold their own. Two players scored big checkmates, and Kasaun was hanging in there against a much higher-rated opponent. Even if he could pull off an upset, the Rooks knew

it probably wouldn’t be enough: their first match that round had ended in a draw.

A few minutes later, Maurice heard shouts at the end of the hallway. “Mr. Ashley, Mr. Ashley!” After a long battle in the endgame, Kasaun had defied the odds and beaten Dalton’s top player. To everyone’s shock, the leading teams had faltered, paving the way for the Raging Rooks to tie for first place. The players erupted in high fives, hugs, and cheers. “We won! We won!”

In just two years, the poor kids from Harlem traveled the distance from novices to national champions. The biggest surprise isn’t that the underdogs won—it’s why they won. The skills and strategies they developed to make that leap would eventually earn them much more than chess titles…

There’s a widely held belief that greatness is mostly born—not made. That leads us to celebrate gifted students in school, natural athletes in sports, and child prodigies in music. But you don’t have to be a wunderkind to accomplish great things. My goal is to illuminate how we can all rise to achieve greater things.

As an organizational psychologist, I’ve spent much of my career studying the forces that fuel our progress. What I’ve learned might challenge some of your fundamental assumptions about the potential in each of us.

In a landmark study, psychologists set out to investigate the roots of exceptional talent among musicians, artists, scientists, and athletes. They conducted extensive interviews with 120 Guggenheim-winning sculptors, internationally acclaimed concert pianists, prizewinning mathematicians, pathbreaking neurology researchers, Olympic swimmers, and world-class tennis players—and with their parents, teachers, and coaches. They were stunned to discover that only a handful of these high achievers had been child prodigies.

Among the sculptors, not even one was identified as having special abilities by elementary school art teachers. A few of the pianists won big competitions before turning nine, but the rest only seemed gifted when compared to their siblings or neighbors. Although the mathematicians and neurologists generally did well in elementary and middle school, they didn’t stand out among the other strong students in their classes. Hardly any of the swimmers set records early on; the majority won local meets but not regional or national championships. And most of the tennis players lost in the early rounds of their first tournaments and took several years to emerge as top local players. If they were singled out by their coaches, it was not for unusual aptitude but unusual motivation. Their motivation wasn’t fixed; it tended to begin with a coach or teacher who made learning fun. “What any person in the world can learn, almost all persons can learn,” the lead psychologist concluded, “if provided with appropriate… conditions of learning.”

Recent evidence underscores the importance of conditions for learning. To master a new concept in math, science, or a foreign language, it typically takes seven or eight practice sessions. That number of reps held across thousands of students, from elementary school all the way through college.

Of course, there were students who excelled after fewer practice sessions. But they weren’t faster learners—they improved at the same rate as their peers. What set them apart was that they showed up to the first practice session with more initial knowledge. Some students got a boost from already having a grasp on related material. Others had parents teach them early or got a head start teaching themselves. What look like differences in natural ability are often differences in opportunity and motivation.

When we judge potential, we make the cardinal error of focusing on starting points—the abilities that are immediately visible. In a world obsessed with innate talent, we assume the people with the most promise are the ones who stand out right away. But high achievers vary dramatically in their initial aptitudes.

You can’t tell where people will land from where they begin. With the right opportunity and motivation to learn, anyone can build the skills to achieve greater things. Potential is not a matter of where you start, but of how far you travel. We need to focus less on starting points and more on distance traveled.

For every Mozart who makes a big splash early, there are multiple Bachs who ascend slowly and bloom late. They’re not born with invisible superpowers; most of their gifts are homegrown or homemade. People who make major strides are rarely freaks of nature. They’re usually freaks of nurture.

Neglecting the impact of nurture has dire consequences. It leads us to underestimate the amount of ground that can be gained and the range of talents that can be learned. As a result, we limit ourselves and the people around us. We cling to our narrow comfort zones and miss out on broader possibilities. We fail to see the promise in others and close the door on opportunities. We deprive the world of greater things.

Stretching beyond our strengths is how we reach our potential and perform at our peak. But progress is not merely a means to the end of excellence. Getting better is a worthy accomplishment in and of itself. I want to explain how we can improve at improving…

The Right Stuff

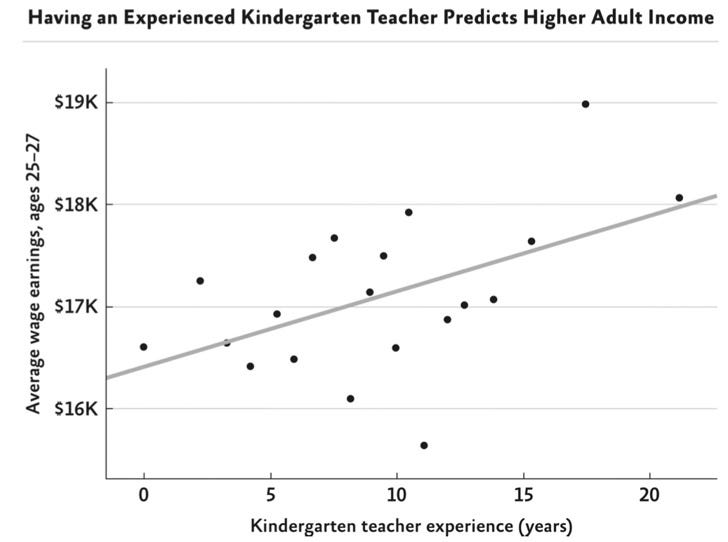

In the late 1980s, around the same time that the Raging Rooks were learning chess in Harlem, the state of Tennessee launched a bold experiment. At 79 schools—many of which were low-income—they randomly assigned over 11,000 students to different classrooms in kindergarten through third grade. The original goal was to test whether smaller classes were better for learning. But an economist named Raj Chetty realized that since both students and teachers were randomly assigned to classrooms, he could go back to the data to analyze whether other features of classrooms made a difference…

The Tennessee experiment contained a startling result. Chetty was able to predict the success that students achieved as adults simply by looking at who taught their kindergarten class. By age 25, students who happened to have had more experienced kindergarten teachers were earning significantly more money than their peers…

To figure out what students were carrying with them from kindergarten into adulthood…In fourth and eighth grade, the students were rated by their teachers on some other qualities. Here’s a sample:

Proactive: How often did they take initiative to ask questions, volunteer answers, seek information from books, and engage the teacher to learn outside class?

Prosocial: How well did they get along and collaborate with peers?

Disciplined: How effectively did they pay attention—and resist the impulse to disrupt the class?

Determined: How consistently did they take on challenging problems, do more than the assigned work, and persist in the face of obstacles?

When students were taught by more experienced kindergarten teachers, their fourth-grade teachers rated them higher on all four of these attributes. So did their eight-grade teachers. The capacities to be proactive, prosocial, disciplined, and determined stayed with students longer—and ultimately proved more powerful than early math and reading skills. When Chetty and his colleagues predicted adult income from fourth grade scores, the ratings on these behaviors mattered 2.4 times as much as math and reading performance on standardized tests.

Think about how surprising that is. If you want to forecast the earning potential of fourth graders, you should pay less attention to their objective math and verbal scores than to their teachers’ subjective views of their behavior patterns. And although many people see those behaviors as innate, they were taught in kindergarten. Regardless of where students started, there was something about learning these behaviors that set students up for success decades later.

Acting Out of Character

When Aristotle wrote about qualities like being disciplined and prosocial, he called them virtues of character. He described character as a set of principles that people acquired and enacted through sheer force of will. I used to see character that way too—I thought it was a matter of committing to a clear moral code. But my job is to test and refine the kinds of ideas that philosophers love to debate. Over the past two decades, the evidence I’ve gathered has challenged me to rethink that view. I now see character less as a matter of will, and more as a set of skills.

Character is more than just having principles. It’s a learned capacity to live by your principles. Character skills equip a chronic procrastinator to meet a deadline for someone who matters deeply to them, a shy introvert to find the courage to speak out against an injustice, and the class bully to circumvent a fistfight with his teammates before a big game. Those are the skills that great kindergarten teachers nurture—and great coaches cultivate.

When Maurice Ashley assembled his chess team for the national championships, a student named Francis Idehen wasn’t one of the best eight players. Maurice picked him anyway due to his character skills. “Another kid was a superior chess player,” Francis tells me, “But he hadn’t developed the emotional self-regulation that Maurice felt was important.”

And when the Raging Rooks fell behind in the penultimate round of nationals, Maurice Ashley didn’t pull out a book of secret plays. He didn’t talk to them about strategy at all. “I reminded them about discipline,” he notes—a skill they’d been practicing together for two years.

Their character skills caught the eye of the legendary chess coach Bruce Pandolfini, who had guided multiple protégés to national and world championships. After watching the Raging Rooks march to victory, Pandolfini marveled:

Nothing fazed them. Most kids under pressure will start hurrying a little bit or showing their feelings, but not them. They took their time, and they were absolutely poker-faced at the board. I’ve never seen kids that age so cool. They were like professionals.

If a knight on the chess board was a Trojan horse, inside it Maurice had smuggled an army of character skills. They helped the Raging Rooks surge as their opponents floundered. “He was always conveying life lessons without being heavy-handed,” Francis says. “It was less about executing a chess plan than understanding of self and mastery of self. That was pivotal in my life…”

Sure enough, evidence shows that although kids and novices learn chess faster if they’re smarter, intelligence becomes nearly irrelevant in predicting the performance of adults and advanced players. In chess—like in kindergarten—the early advantages of cognitive skills dissipate over time. On average it takes over 20,000 hours of practice to become a chess master and over 30,000 to reach grandmaster. To keep improving, you need the proactivity, discipline, and determination to study old games and new strategies.

Character skills do more than help you perform at your peak—they propel you to higher peaks. As Nobel laureate economist James Heckman concluded in a review of the research, character skills “predict and produce success in life.” But they don’t grow in a vacuum. You need the opportunity and motivation to nurture them.

If You Build It, They Will Climb

When people talk about nurture, they’re typically referring to the ongoing investment that parents and teachers make in developing and supporting children and students. Helping them reach their potential requires something different. It’s a more focused, more transient form of support that prepares them to direct their own learning and growth. Psychologists call it scaffolding.

In construction, scaffolding is a temporary structure that enables work crews to scale heights beyond their reach. Once the construction is complete, the support is removed. From that point forward, the building stands on its own.

In learning, scaffolding serves a similar purpose. A teacher or coach offers initial instruction and then removes the support. The goal is to shift the responsibility to you so you can develop your own independent approach to learning. That’s what Maurice Ashley did for the Raging Rooks. He set up temporary structures to give them the opportunity and motivation to learn.

When he started teaching chess, Maurice saw other instructors line up all the pieces to teach the standard opening moves: King’s pawn forward two spaces, followed by knight up one and diagonal one. But he knew learning the rules could be boring, and he didn’t want kids to lose interest. So when he first showed up to introduce the game to a group of sixth graders, he did it backward. He put a handful of pieces on the board and began at the endgame. He taught his students different ways to checkmate their opponents. That structure was their first bit of scaffolding.

It’s often said that where there’s a will, there’s a way. What we overlook is that when people can’t see a path, they stop dreaming of the destination. To ignite their will, we need to show them the way. That’s what scaffolding can do.

By teaching the game in reverse, Maurice lit a fire of determination. Once students knew how to corner a king, they had a route to victory. Once they had a way to win, they had a will to learn. “You don’t tell kids, ‘Well, you’re going to learn patience and determination and fortitude,’ cause they’ll fall asleep right away,” he laughs. “You say this, ‘This game is fun. Let’s go—I’m gonna beat you…. stir their spirit, their competitive fire. They sit down, they start learning the game, and as they become hooked, and they lose a game, they want to win.’” It wasn’t long before Kasaun Henry would lie in bed at night, imagine 64 squares on his ceiling, and play out entire matches in his mind.

Maurice also introduced scaffolding for the players to support one another’s development. He taught them creative ways to share techniques: they drew cartoons about chess moves, wrote science fiction stories about chess matches, and recorded rap songs about commanding the center of the board. They were learning to treat a solitary game as a prosocial exercise in teamwork. When a player cried at nationals, it wasn’t because he lost; he was devastated that he had let his teammates down.

As they gelled into a team, the players started taking the motivation and opportunity to learn into their own hands. They held one another accountable for recording every move of their games on score sheets so the whole group could learn from individual mistakes. They weren’t worried about being the smartest player in the room—they were aiming to make the room smarter.

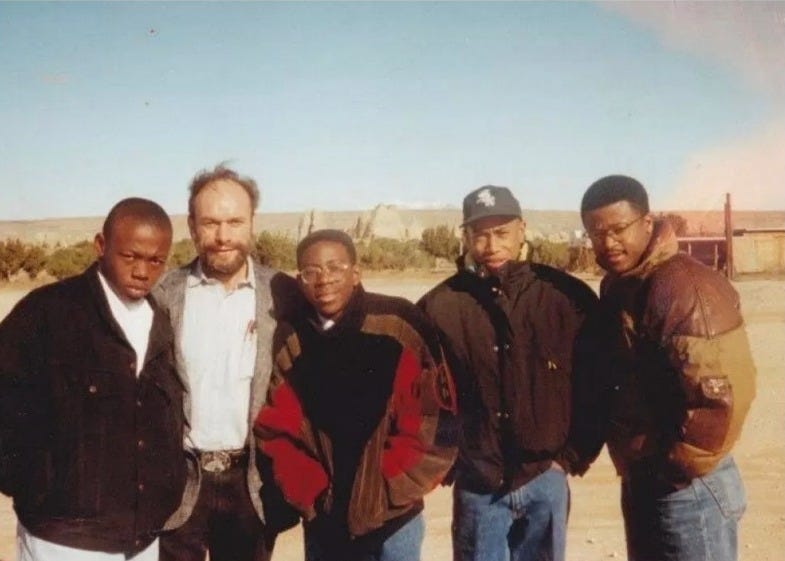

The previous year, at their first nationals, the Raging Rooks had finished in the top ten percent despite being short on players due to budget constraints. When Maurice set a goal for them to win the following year, it was the players who took the initiative to plan. Now that they had the skill, they had the will. They created their own makeshift chess camp, spending the summer practicing and reading books. They cajoled Maurice into dedicating his summer off to their training. They had moved into the driver’s seat.

In an ideal world, students wouldn’t have to rely on one coach for these opportunities. The scaffolding Maurice created was a substitute for a broken system. One parent told him that when she saw her son play chess, she realized she hadn’t believed in him. He wasn’t just helping his players reach their potential—he was helping their parents and teachers recognize it too.

Few of us are lucky enough to have a coach like Maurice Ashley. We don’t always have access to the ideal mentors, and our parents and teachers aren’t always equipped to provide the right scaffolding…

The very doors that societies are supposed to open to people with great potential are often wrongly closed to those who have faced the greatest obstacles. For every longshot who breaks through after being underrated or overlooked, there are thousands who never get a chance…By changing systems that prematurely write people off, it’s possible to improve the odds for underdogs and late bloomers…

That’s what the Raging Rooks did. Their success played a role in changing the face of chess. Coaches estimate that since they burst onto the scene, the proportion of racial minorities at national tournaments has quadrupled. Maurice has become an international spokesman for chess as a vehicle for building character, and the movement he helped to fuel now features chess programs in low-income schools across America. One chess nonprofit has single-handedly taught more than half a million kids.

There’s no reason to believe the magic is limited to chess. If debate happened to be Maurice’s passion, he’d be guiding students to anticipate counterarguments and help one another refine rebuttals. What makes a difference is not the activity but the lessons you learn. As Maurice says, “The achievement is in the growing.”

Thanks to the opportunity and motivation that Maurice set in motion, the Raging Rooks applied their character skills beyond chess. The discipline they exercised to resist the pull of shortsighted moves came in handy for resisting gangs and drugs. The determination and proactivity they marshaled to memorize patterns and anticipate moves also applied to studying for tests. The prosocial skills they developed practicing together and critiquing each other helped them become great collaborators and mentors themselves.

Most of the players managed to rise above their circumstances. Jonathan Nock came from a rough neighborhood where he was mugged on a basketball court during the winning season; he’s now a software engineer and the founder of a cloud solutions company. Francis Idehen had dodged stabbings and shootings on his walk to school; he landed an economics degree from Yale, an MBA from Harvard, and jobs as the treasurer of America’s largest utility company and COO of an investment firm. Kasaun Henry went from being homeless and being recruited by a gangster to earning three master’s degrees and becoming an award-winning filmmaker and composer. “Chess developed my character,” Kasaun reflects. “Chess increased my concentration and focus.... Chess ignited me. Someone lit a star that will keep burning as long as I live.”

Along with building successful careers, chess encouraged the Raging Rooks to create opportunities for others. Growing up around the corner from four crack houses, Charu Robinson had multiple friends who were murdered and a number who went to jail. After beating one of Dalton’s best players at nationals in 1991, Charu won a full scholarship to Dalton. He ended up earning a criminology degree and becoming a teacher. He wanted to pay forward what he’d learned.

In 1994 the principal of another Harlem middle school three blocks away from JHS 43 begged Maurice to coach their Dark Knights. Over the next two years, their teams of boys and girls won back-to-back national championships. By then Maurice was ready for the next step on his mission to make history. He took a break from coaching to work on his own game. In 1999 Maurice became the first African American chess grandmaster ever.

That year, with a new coach, the Dark Knights won their third national title. Their assistant coach was Charu Robinson—who went on to teach chess to countless children in schools throughout the city. The Raging Rooks weren’t just single roses growing from cracks in the concrete. They tilled the soil for many more roses to bloom.

When we admire great thinkers, doers, and leaders, we often focus narrowly on their performance. That leads us to elevate the people who have accomplished the most and overlook the ones who have achieved the most with the least. The true measure of your potential is not the height of the peak you’ve reached, but how far you’ve climbed to get there.

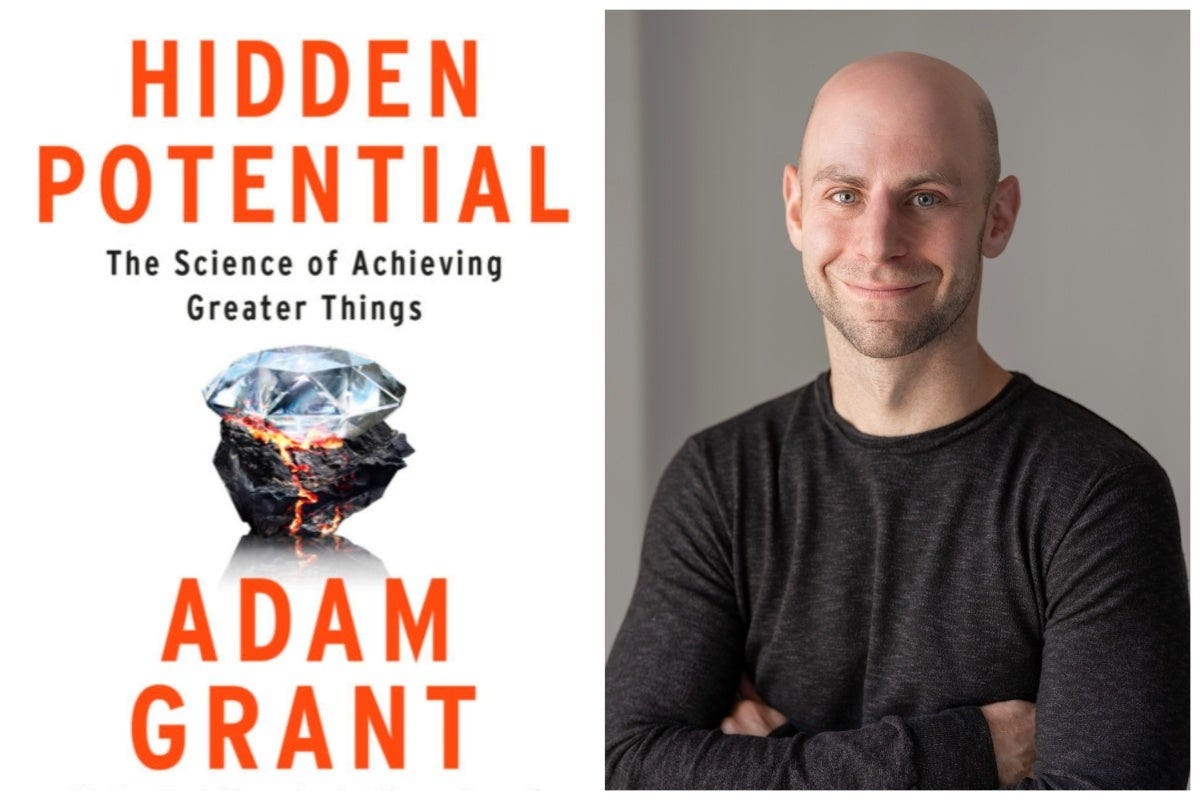

Adam Grant is an organizational psychologist and bestselling author who explores the science of character, connection, culture, and change. As an organizational psychologist, he is a leading expert on how we can find motivation and meaning, rethink assumptions, and live more generous and creative lives. He has been recognized as the world’s #2 most influential management thinker and one of Fortune’s 40 under 40.

He is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of 6 books that have sold millions of copies and been translated into 45 languages: Hidden Potential, Think Again, Give and Take, Originals, Option B, and Power Moves. Adam hosts the TED podcasts Re:Thinking and WorkLife, which have been downloaded over 90 million times. He has more than 10 million followers on social media and features new insights in his free monthly newsletter, GRANTED.

Adam, this is the part of “hidden potential” church folks should be taping to the pulpit. Stop preaching that greatness is born in a chosen few when the whole gospel is about fishermen, tax collectors, and nobodies who didn’t make the cut for anyone’s “gifted program.” The Raging Rooks didn’t win because they were prodigies, they won because someone lit a fire and built them a ladder. Most of us aren’t missing talent, we’re missing scaffolding. The kingdom of God isn’t built on early aptitude, it’s built on people who take what little they’re given and climb farther than anyone thought possible.