Exclusive Excerpt: Britt Hartley on Awe

PLUS: Britt joins Rainn on the Soul Boom podcast to talk No-Nonsense Spirituality

Greetings, fellow sentient stardust beings rocketing through late-stage capitalism!

This week on the Soul Boom podcast, we welcome the brilliant, bold, soul rebel Britt Hartley.

Britt is a self-described “mystic atheist”—a spiritual director, Sufi initiate, and former seminary teacher who lost her faith in God while getting her PhD in theology. You read that right.

In this episode, she and Rainn dig into everything from deconstructing faith to psychedelic awakenings to the possibility of a moral life without metaphysical certainty. It’s funny but deeply thought-provoking.

By the end, the conversation keeps circling back to something both Britt and Rainn hold dear: Awe. That soul-opening feeling that something vast and sacred is unfolding all around us—and within us.

Now, with Britt as an avowed atheist, you might be wondering about the “mystic“ part of her self-description. After all, she and Rainn aren’t exactly aligned on the subject of the Notorious G.O.D..

Rainn believes in a loving, conscious, infinite, and Unknowable Essence as the Source of reality. Britt sees “God” as a human metaphor for the transcendent in our shared reality.

Yet, what Britt and Rainn do share is a belief that we still need spiritual tools in a world where the religious orders of millennia past are crumbling before our eyes. They also believe we humans share a common hunger for meaning, depth, and connection. And both Britt and Rainn have faith in the healing power of awe, story, and service.

Those shared values are clear in this excerpt from Britt’s book, No Nonsense Spirituality. It’s a sharp and moving reflection on how awe can ground us—whether or not we believe in anything beyond.

With no-nonsense—just lots of love,

The Soul Boom Team

Awe and Contemplation

From No-Nonsense Spirituality

by Britt Hartley

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed. This insight into the mystery of life, coupled though it be with fear, has also given rise to religion. To know that what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling, is at the center of true religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I belong in the ranks of devoutly religious men.”1

—ALBERT EINSTEIN

Awe is something you have probably experienced but is hard to define. I feel it in ancient cathedrals, dusty books, and deep conversations. Awe is an intense emotional experience often characterized by a sense of wonder, amazement, and reverence in the presence of something profound, often leaving a person feeling humbled and deeply moved. It registers differently in our brain than feeling joy or happiness. This place is the center of spirituality, the experience that starts religions rather than the religions themselves. For some people this is hearing a song that makes you cry, a child being born, a movie that inspires you, the view of Earth from space, looking at the stars, a live concert, partaking of mushrooms, art in all its forms, truly looking in someone’s eyes, a story told around a campfire, the view from atop a mountain, meditation, realizing on a walk that the redwood tree is older than you and will outlive you…all different experiences that induce deep feelings of awe. It’s necessary to know that we are a part of something that is so much bigger than us. It’s like there’s this whole story of life on earth and you get to pop your head up and look around and experience the universe as you. In this way, awe can be considered an altered state of consciousness and one that we can curate more often.

For a long time, awe was ignored by modern science and psychology as “woo,” but in 2003, there was a landmark paper where the researchers gathered every study that had been done on the concept of awe and began to organize it, culminating in a fantastic book called Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder by Dacher Keltner.² In this book, the researchers suggested that while the oncoming of a feeling of awe is unique and varied, the two effects that stand out most consistently are the “perception of vastness” and the “need for accommodation.” Awe is really about vast things that transcend your understanding of the world, which you need to accommodate to your understanding of reality. Perceived vastness can come from observing something literally physically large such as the Grand Canyon, or through an encounter with something or someone that is profound, such as being presented with a complex idea like the theory of evolution. It’s an idea or experience that interrupts our usual line of thinking, turns off our default mode ego driven brain, and reminds us of how connected we are.

Some people call this “God.”

A quick side tangent here on how secular spirituality approaches the God word, a word that I come across every day in my work. A good guide is to gauge whether a person is using that word to describe a subjective experience or an external reality. If someone walks into a sacred space and says, “I feel God here,” there’s no need to be the annoying “actually…” kind of person. They are describing a feeling, a subjective experience, with sounds and symbols because that’s all we have to be able to explain. I know that feeling. I can meet them in that place and say I feel God here too. Mystics use that word, but don’t define it and certainly don’t try to contain it in the ways that religions do. After all, everyone’s definitions of God are so different, I can meet that word on my own terms too. Even the most ardent scientific atheists will say they believe in the God of Spinoza, or the God of Einstein, which is something like the natural order of things, mathematics, the patterns of nature, or the mystery of life. God for me means collective consciousness, something that is bigger than me, but that I am a part of. I am to God as bees are to a hive. A single bee contributes less than a teaspoon of honey in its lifetime and lives only a few brief months. But a hive of bees affects an ecosystem for miles around, in ways that a single bee could not possibly comprehend. A hive is connected to everything. The single bee is almost insignificant in comparison, and still part of the hive, dancing to communicate to the other bees.

The problem is when a person tells me God says gay people are going to hell, or God created the universe and this is his plan, or God wrote this book, these are not just subjective feelings. These are metaphysical statements about the nature of the universe. When we begin to use subjective experience to describe objective realities, we must be cautious. Even if one religious worldview were actually correct, statistically, it wouldn’t be yours. That’s just math. Humans have been creating gods and religions for at least tens of thousands of years if not hundreds of thousands of years. The best tool we’ve ever come up with as humans to actually gauge objective reality is science, and when it comes to statements of metaphysics about the universe, science must be given first priority. There are millions of examples of religious answers to metaphysical questions that are now better answered by science. In this space, the balance is to preserve the feeling of awe that people have called God and separate it from all the doctrines that we have ascribed to God.

The experience of “awe” or “God” may make us feel a “need for accommodation” when it violates our normal understanding of the world. Our brains naturally think negatively; a bias we likely inherited because it helped us survive better. It’s easy and natural for our brains to freak out about things that we know deep down don’t ultimately matter. It’s very normal to think for three days about a side glance from someone, spiral about a comment someone made on Instagram, or get in a bad mood because of a stain on our favorite shirt. But having regular spiritual experiences about the big picture can break us out of that really depressive way of thinking. Our brains actually rewire, and we adjust our mental structures. With experiences of awe, we are more skeptical of bad arguments, we’re in a better place to make adjustments in our life rather than get stuck in our usual way of thinking, we feel more connected to others, we’re more willing to let go of grudges, and it just gives us a break from the usual negative neurotic way our brains work. This shift in perspective is linked to increased prosocial behaviors and acts of kindness, indicating that awe may play a role in promoting empathy and social cohesion. It may not even be unique to humans. We cannot know what a primate is feeling when they collectively stop to look at a sunset, but researchers like Jane Goodall believe that the experience of being amazed at something outside yourself is a phenomenon that we share with at least our evolutionary cousins.

Experiencing awe can have profound psychological effects. Positive emotions, such as gratitude, are often associated with awe-inspiring moments. Awe can lead to a sense of humility and decreased self-centeredness, prompting individuals to focus less on their own concerns and more on the well-being of others, similar to an ego death on psychedelics. In a study led by Keltner, participants at a Yosemite National Park scenic overlook, when prompted to create artistic doodles, consistently depicted themselves as smaller in scale compared to participants in downtown San Francisco. This trend implies a reduced sense of self-importance among those immersed in the natural beauty of Yosemite. The feeling of induced awe at looking out at Yosemite decreases the feeling that you are the center of the universe, coming through in how they drew themselves on a piece of paper.³ In a separate experiment, participants instructed to admire towering eucalyptus trees requested lower compensation for their involvement compared to those directed to observe an academic building. Furthermore, the former group demonstrated greater willingness to assist in picking up pens accidentally dropped by a study organizer during a simulated spill.⁴

This is where neuroscience is helpful. We can see the default mode network, where self-representation takes place, as quiet during moments of awe. In the pop psychology world, people are told to focus on what they are grateful for. Often this looks like shoving down and suppressing negative emotions to try and force oneself to be grateful for what one has. An experience of awe, in contrast, is the repository of gratitude itself where it flows naturally, rather than forcing it through a journal challenge from Oprah because we should be more grateful.

One of the purposes of religion was to induce these experiences of awe. Imagine taking a pilgrimage to Mecca as a Muslim. The sight of millions of pilgrims from around the world converging at the Kaaba, the most sacred site in Islam, creates a powerful sense of unity and awe. There’s something beautiful when you’re visiting a Muslim country, watching people pause, even mid-transaction in the market, to hear a call to something bigger than themselves. The Kumbh Mela, a massive gathering held every 12 years, involves millions of Hindus bathing in the sacred rivers of India to cleanse and renew themselves. The Golden Temple in Amritsar, India, is a central place of worship for Sikhs. The temple’s striking architecture, the sound of hymns, and the communal practice of serving food to all, regardless of background, inspire a sense of unity. The Sun Dance, practiced by various Native American tribes, involves physically demanding rituals, including fasting and body piercing, to connect with the spiritual world. The pain endured and the communal participation evokes spiritual transformation. Shamans from various cultures lead groups in tribal drumming and psychedelic partaking, promoting a kind of communal trance that transcends everyday concerns. Visualize walking through the Sistine Chapel marveling at images of creation on ceilings, ending at a wall where Christ is pointing up for those with good souls with one hand, and pointing to the scar on his side with his other hand, pushing down those who know they have lived unworthy of their own sense of morality. Contemplate the literal “come to Jesus” moment as one weighs their own soul and the meaning of life in this moment. This is the best of what religion can do, provide opportunities for spiritual experience individually and communally through story, art, dance, architecture, and ritual.

Fast forward to today and awe is about the last thing one feels in church. In my own native religion, church buildings are all the same—the same carpet, the same stock photos on the walls, long bereft of any true creative expression or authenticity. Even Sunday School is no longer a place for real discussion, it is simply a call-and-response ritual where a question is asked by a teacher, and the usual answer is given by the audience in an attempt to make us feel safe and even superior. Most words over the pulpit today in America are political, hypocritical, prosperity gospel driven, us versus them—apocalyptic garbage, which is hilarious because how you get that from a radical homeless man named Jesus is a testament to human idiocy.

To encounter awe, according to Keltner, one should seek out what he refers to as the “eight wonders of life.” Among these, the more prevalent sources include nature, music, visual design, and moral beauty, particularly instances where individuals extend help to others. Less frequent yet deeply impactful wonders encompass “collective effervescence”—the intense shared enthusiasm witnessed in, for example, a soccer stadium or concert, spiritual experiences, epiphanies that reshape one’s worldview through unexpected revelations, and, inevitably, the profound moments of life’s commencement and conclusion, such as births and deaths. If you’re a human who is reading this, I’d argue you’ve experienced this feeling at least once in your life, at a time and place unique to you and your life story. The trick is to continue to dose these experiences more regularly and intentionally.

Contemplation Practice

By reclaiming our access to awe, we reconnect to this deep well of pure spiritual water rather than the rancid water being sold by organized religions today for a price. Rather than walking around and waiting for awe to dance across a table for you, one can seek out these experiences. As we do so, we make the shift from just one moment (awe) to a way of life (contemplation practice). A contemplation practice is simply noticing how you experience awe and making a habit out of it.

A usual question I may ask in spiritual direction is: “How do you experience spirituality, do you have a practice in your life?” A common response is “I don’t have a contemplation practice or a spiritual life. I know I should meditate but my kids are way too loud. I can never do it and I’m too inflexible to sit on a mat. I’m so busy I don’t have any spiritual practice at all.” What this usually implies is that the client has a very narrow sense of what a contemplative practice is, often caused by being raised in a patriarchal religion. In patriarchal religions, the rites and rituals of spirituality are written by men in a priest class supported by the people, and thus often include requirements for scripture study, meditation, and various hoops to jump through provided by the priestly class. What this means is that a modern person may conclude that they are not spiritual at all.

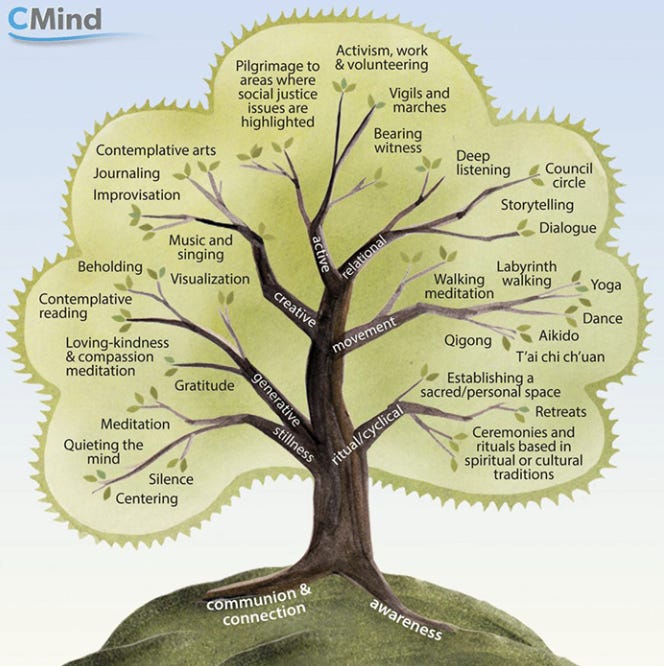

To really get an idea of the contemplative practice that calls you, we have to get a wider sense of the ways in which humans experience awe and transcendence. For this exercise, I defer to the Contemplation Tree from the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society, based on their studies that organized many of the ways that humans turn for connection. It is a perplexing thing how we can fly through the universe on a space rock in a clump of cells that are somehow self-aware and still go years on autopilot just reacting like a robot to the pressures of the world around us. Contemplation is what we do to wake up in a world that is asleep. The benefit to taking on this path in the realm of secular spirituality is that you get to choose the actions that fit you best.

1. Stillness Practices. Is quiet time your best time to reconnect? Consider stillness practices that focus on quieting the mind and body in order to develop calmness and when that calmness comes, the insight and connection come with it. When we get out of the crashing waves of our wandering attention and reactive emotions, we can drop into a deep ocean full of life and calm that lies underneath. Meditation apps and centering practices are great for learning how to drop into this space. For me, it often looks like leaving a little earlier to my children’s bus stop so that I can sit quietly in my car, breathe, and be prepared for all the emotions my children come home with. It’s a quiet moment where I can wake myself up to the meaning of this moment of connection, this after-school ritual between mother and child, that forms a relationship that is significant to me. When I miss my pre-bus stop breath, I often feel regret that the moment of opportunity passed because I was lost in my head, my emotions, or my phone.

2. Generative Practices. Generative Practices come in many different forms (i.e. prayers, visualizations, chanting) but share the common intent of generating thoughts and feelings on purpose. We will see concepts of God more available here, such as in Christian-centering prayer, some kind of devotion ritual to God or ancestors, or chanting phrases about love or gratitude. It’s meant to generate a certain thought rather than just being still. Visualization exercises can be done with mystics, but also in sports or in business. By focusing the mind towards a certain state, we can generate the thoughts and feelings we want to have. Loving-kindness meditations are a great example of this where we are encouraging the mind to go to a state where we want to be, one that evokes awe at the nature of being, and kindness towards other conscious creatures.

3. Creation Process Practices. These practices are for people who connect best when their creative energy is flowing through them whether it be through music, art, sand mandalas, singing, journaling, pottery, or DIY projects. A dear friend of mine is this type where, when we go up to a cabin for retreats, she brings a drum and art instruments and gets into that place where expression flows through her and wants to create. She can both create and watch herself as she creates, tapping into the magic of whatever life is. Gardening is a great one here if you are creative, making a spiritual temple out of growing something with the earth. Until I met with my own spiritual directors, I had no idea that writing, even if only a message I wanted to put on social media, was “spiritual” or could even be my contemplative practice. No one had ever told me that writing was a spiritual contemplative practice.

4. Movement Practices. Movement can be for the sake of movement or physical exercise but it can also be for transcendence. This includes one of my favorite spiritual practices which is labyrinth walking—walking a maze to a center to symbolize opening up to what’s going on deep within, sitting in the center, and then walking back out of the maze with the intention of reintegrating with the world. Martial arts, tai chi, Sufi dancing, contemplative movement, walking meditations, long bike rides, yoga, Wim Hof style hot and cold therapy…for some people getting their bodies involved is how they tap into that feeling of awe at being alive. These are the kinds of people who don’t hike or bike because they hate their bodies; it’s how they show up for themselves over and over again. The memory that most comes to mind is seeing local surfers in coffee shops grabbing breakfast before going surfing at 5 AM, just to see the sunrise and ride a wave before starting the day. It absolutely can be claimed as a contemplative practice.

5. Activist Practices. This is an increasingly popular choice for Gen Z spirituality, as social justice work becomes the way that they become a part of something bigger than themselves. Vigils, marches, social justice work, pilgrimages, bearing witness, environmental battles, LGBTQ+ work—these are all getting involved in causes that are meaningful in some way. One of the most profound experiences I ever had was walking in the Boise Pride Parade with Mormons Building Bridges, an organization that seeks to provide aid for gay Mormons who have been the recipients of hate speech, persecution, and exile from their Mormon community. I’ll never forget the face of one old man who looked at our sign and burst into tears. I went to hug him and he embraced me so tight, with cries so deep, I could hardly breathe. I never heard his story, I only know by his age and Mormon past, it was likely a doozy. It was one of the most spiritual experiences of my life, where he and I were simply humans, embracing the pain of our shared community and the hope that things would be better. I got the sense that he didn’t get that hug from his family, but it was perhaps healing on a tiny level to get that needed embrace years later from a stranger who was publicly saying, “I’m sorry, it shouldn’t have been this way. What happened to you shouldn’t have happened.” There are many spiritual paths here in service, protest, or work that is the spiritual practice of holding up a lantern of justice to give witness to what shouldn’t be, and shine a light onto the corners of society we’d rather not see. It is sacred work.

6. Ritual/Cyclical Practices. This branch is for those who prefer returning to rituals weekly, monthly, and yearly with practices that keep them returning to themselves. I would include religious observances of the Sabbath here as well as those who integrate the seasons of the earth. Either way it is a specific day on the calendar that calls you to remembrance through a ritual, ceremony, yearly retreat, or solstice. This could be going to the lake on Sundays in the summer with your family or special Christmas traditions. My pagan friends are fantastic at modeling this rhythm for me. One friend in particular holds a bounteous dinner where people bring homemade foods from the earth to celebrate the harvest, held yearly on Hobbit Day in September. People gather, with a pipe in hand, to sing, play instruments, share a fire, eat, recite a poem, and show love to one another at the end of summer. Would a priest call it spiritual? Perhaps not. From first glance it may look like a conglomeration of nerds. But look a little closer and there’s an air of sacredness that calls people to return year after year. Tapping into the earth and its seasons and happenings can give you a heartbeat, a pattern that can help you return to the breath of life.

7. Relational Practices. Relational practices are things like deep listening, reading, writing, acts of service and kindness, storytelling, story hearing, deep dialogues, council circles, podcasts, and even people smoking weed around a fire and talking about life. If you really crave other people as a part of your spiritual life, you’ll need to find ways to integrate this particular spiritual need. When my daughter fell from a window and we spent a summer in the ICU, the first thing I added back to my plate when she returned home was podcasting, not because my podcast listeners really needed me but because I needed the conversation. It was a part of my spiritual life and practice. I experienced awe many times while podcasting where it hit me like a ton of bricks that wow life is amazing. Again this is another area where a religious leader may look at the conversation of women as gossip, but for many people, it is church itself and deserves to be a priority.

So now that we’ve laid some groundwork, the question is how do you experience Awe? What was the last time you were shaken out of your day-to-day grumpy brain? And how can you claim it as your practice, one that calls you to your deepest self? According to the groundbreaking work of Lisa Miller, world expert on spirituality and the brain, one’s spirituality is about 71% determined by our environment. Christmas songs, for example, tend to be more uplifting to those raised Christian. For the children of scientists, nature may be more of a connection. But the other 29% is your innate sense of spirituality, something inherent to being a human, no matter your upbringing. Spirituality is not just a belief, it is a birthright. Like any inherent human attribute, some have a greater or lesser propensity, but this can be strengthened like learning to play music. From Miller, “a significant degree of our capacity to experience the sacred and transcendent—one-third—is inscribed in our genetic code, as innate as our eye color or fingerprints.”⁶ Your ability to feel connected to this story of life somehow, somewhere, is an essential part of your humanity that no one can take from you. Awe is how we remind ourselves of the miracle it is to be awake. Or, to quote Ferris Bueller: life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop to look around once in a while, you could miss it.

So what’s your take, Soul Boomlets?

What does no-nonsense spirituality look like to you?

How do you get your daily dose of Awe?

Endnotes:

Rowe, David E., and Robert J. Schulmann. Einstein on Politics: His Private Thoughts and Public Stands on Nationalism Zionism, War, Peace, and the Bomb. Princeton University Press, 2013, 229.

Keltner, Dacher. Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life. Penguin Books, 2024.

Ibid., 33–34.

Ibid., 134.

Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. “The Tree of Contemplative Practices.” 2021, https://www.contemplativemind.org/practices/tree

Miller, Lisa, and Esmé Schwall Weigand. The Awakened Brain: The New Science of Spirituality and Our Quest for an Inspired Life. Random House, 2021, 58.

Britt Hartley is a secular spiritual director, certified through the two-year program at the Center for Non-Religious Spirituality, and a former seminary teacher with a Master’s degree in Theology focused on the future of American religion. A self-described “mystic atheist,” she is also an ordained Sufi and a coach specializing in religious trauma and faith deconstruction. Raised Mormon, Britt began questioning her beliefs early and ultimately stepped away from traditional faith during her PhD studies. She is the author of the bestselling No Nonsense Spirituality: All the Tools, No Belief Required, a practical guide for seekers craving depth, connection, and spiritual tools—without religious affiliation. Britt lives in Boise, Idaho, where she cultivates a vibrant community centered on secular mysticism, philosophy, parenting, and creative living.

Good and punny: “Aww we love to hear it” in response to a piece on “awe.”

I've been looking forward to this one for weeks! Britt is the best and her book is excellent!