Penn Badgley on Lineage

A moving essay from Crushmore — the new book from the Podcrushed team!

If you’re a “Soul Crusher” — that is if you’re a fan of both Soul Boom AND Podcrushed — then this week’s Dispatch is especially for you!

That’s because, while it’s an off-week for the Soul Boom podcast, we’re sharing something special from our dear friends over at Podcrushed — the tender, hilarious, and heartfelt show hosted by Penn Badgley*, Nava Kavelin, and Sophie Ansari**, where they explore that wild inner landscape known as adolescence. Each episode dives into the stories that shaped us in our teen years and the memories that quietly continue to make us who we are.

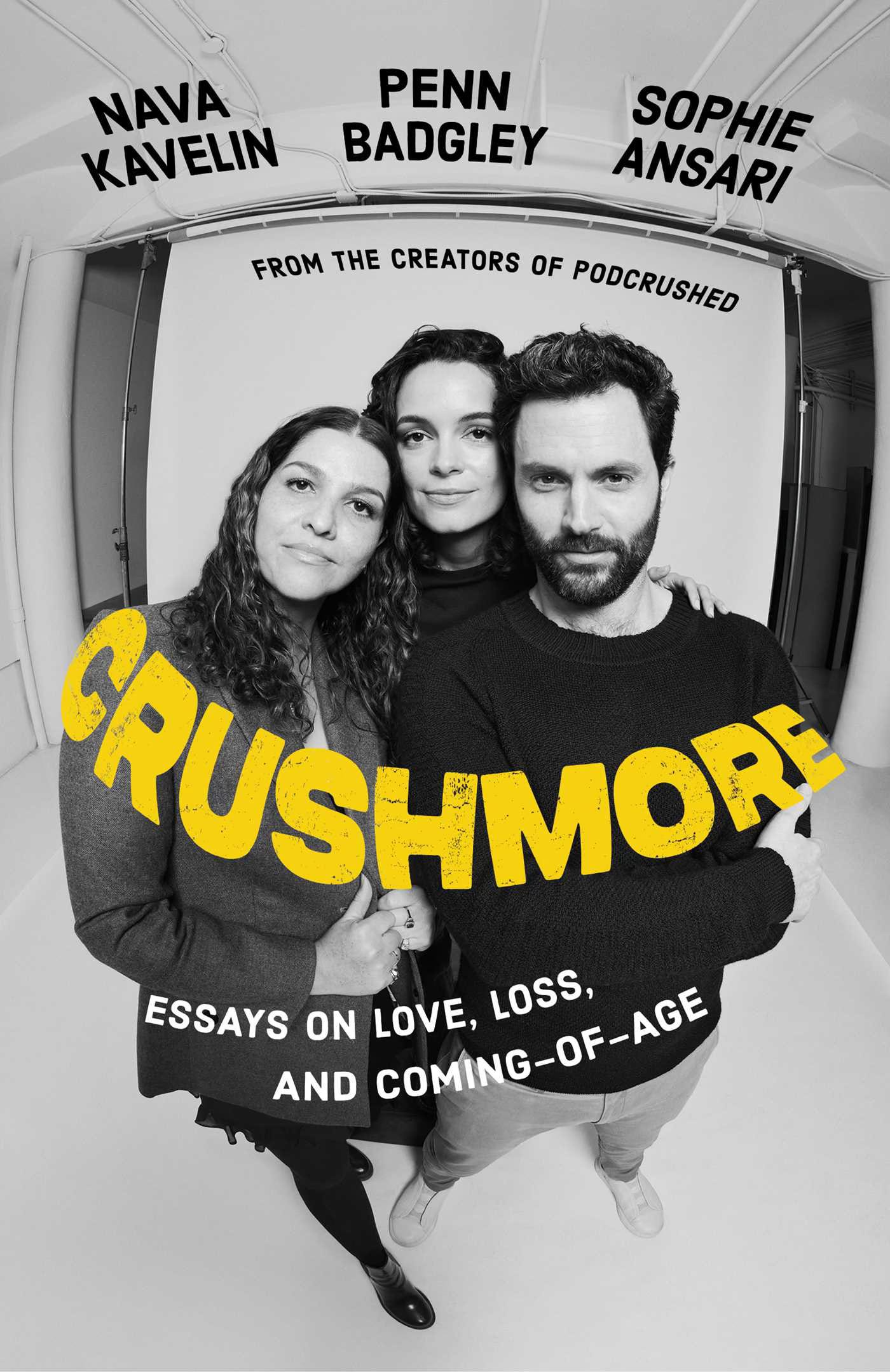

Recently, the Podcrushed trio gathered all of that humor, wisdom, and emotional archaeology and channeled it into a new collection of personal essays: CRUSHMORE: ESSAYS ON LOVE, LOSS, AND COMING-OF-AGE — a reflection on the long, crooked road to growing up (which, it turns out, doesn’t end at thirteen… or even thirty-three). Crushmore has already become a national bestseller! People love it and we think you will as well.

So this week, we’re thrilled to share “Lineage,” an essay from Crushmore by Penn Badgley that reaches back into childhood, ancestry, estrangement, and the mysterious inheritance each of us carries—the wounds and wonders we never asked for, and the strange, beautiful work of making something whole out of what we’ve been given.

With love, curiosity, and just a hint of middle-school nostalgia (though we certainly don’t want to relive it),

The Soul Boom Team

*By the way, Penn has been on not one, but two episodes of Soul Boom with Rainn. Check ‘em out!

**Also, you know that cool little DIY-style animated intro we have for every Soul Boom episode? Sophie made that!

LINEAGE

By Penn Badgley

I’m not an only child.

I have invoked only child privileges and archetypes throughout the entirety of this book to explain my feelings of isolation growing up, but I do have a half sibling with whom I spent zero years living with. My sister—my father’s daughter from his first marriage—was seventeen when I was born, about to go to college, and lived with her mother. She married and had her first child by the time I was seven, making me a child-uncle, which was always a fun little caveat to my only-ness. Our connection as half siblings was our father, and once I was no longer living in the same house as him at twelve years old, my relationship with her would lie totally dormant until I entered my twenties and we reconnected on our own terms (which has been a beautiful and lovely thing).

My father was an only child, and there are almost no other relatives I’ve known through his side of the family. Three of my four grandparents died by the time I was two, save for my mother’s father, an eccentric man whom I knew through stories more than in real life. We traveled to Maryland when he was dying, and his last words to me, as he swam in the liminal spaces of consciousness days from death, were emphatic. He opened his eyes, clenched his hand into a half fist, and said, as though it were the answer to life’s most impossible question: “Do Over.” He nodded, winked, closed his eyes, and I never saw him awake again.

Do Over was the name of the short-lived television series I starred in at fifteen (one where I was working twelve hours a day and whose income allowed me to Rbuy copious amounts of weed and an Audi A4 in cash on my sixteenth birthday). He seemed to be saying, “Ya made it, kid.” I was a tad embarrassed, as my mother’s entire extended family was surrounding us and so many of them knew him much better than I did.

My grandfather served in World War II as a pilot, survived, and then had to live a life afterward like millions upon millions of veterans across the world. Like so many of those millions, substance abuse left a mark on him, his wife, and their kids—my mother and her seven siblings.

The firstborn of the Murphy clan was a pair of twins, Susan and Mary Lou. When the twins were five and my mother was three, Mary Lou drowned. The family arguably never recovered. Dysfunction ruled as their brood grew to half a dozen, and finally the matriarch left the family when my mom was sixteen, without telling anybody. My mother’s mother left all her kids. She said that she was going to the movies one night and never came back. After a few days, the children had to alert their father that their mother was probably gone. My mother then had to raise her younger siblings in many ways. I don’t know how much any of them knew their mom, who didn’t disappear entirely but never reclaimed her status or responsibilities as mother. I certainly never knew her. My maternal grandmother remains to me, and probably to all her children, an enigma. I don’t have a clear image of her in my mind; I don’t know what she looked like. I met her only as an infant, and soon after, she died on Mother’s Day.

Given all this death and estrangement—a family history I neither knew nor understood as a child—I grew up without having much of a place for family in my mind. One doesn’t know what one doesn’t know. In terms of heritage, I had none that I could identify beyond being of Irish and Scottish descent, which didn’t mean anything to me because I didn’t know anyone from Ireland or Scotland. All I knew of either place were cartoonish tropes, which is all children in America were taught in the nineties. Being Irish, as far as I could tell, had something to do with greenness and Guinness, and being Scottish was much less interesting. No, I was American. That was clear, and yet this, too, meant very little to me. Quite the opposite of American exceptionalism, I felt alien for no single reason I could identify, and I accepted this veiled sense of my place in the world as a standard, just like any child does.

Those early childhood years—my orientation to planet Earth—were in Richmond, Virginia. My parents had met and married in Annapolis, Maryland, before we moved to Virginia when I was two, where they founded a construction company together because it was close to where we lived, and cheap. I remember wandering construction sites as a child. The smell of sawdust and drywall is a deep sense memory that takes me right back to my earliest years, ones I can hardly visualize. There I lived an idyllic suburban life, biking quiet, single-lane streets with the neighborhood boys in a brand-new suburban community that had been carved into the woods only a couple years prior. I had three close friends, two of whom lived less than a minute’s walk from my door. There must have been a sense of community there, I suppose, but I can’t remember it. It didn’t stick.

My final year in Virginia, at seven years old, I switched from a small and unremarkable public school not five minutes from our home to a private school whose commute took me across the James River every day. I carpooled with a boy named Caleb who lived at least twenty minutes away, in what felt like a comparatively rural area. Caleb spoke with a Southern accent as thick and magnetic as Matthew McConaughey’s, and like McConaughey (friend of the pod), Caleb relished a good story, many of which he’d tell on the way to school or captivate the class with once we arrived there. He’d laugh and slap his knee with the presence of a man literally ten times his age—one who had been to war, gained and lost lovers, and knew where he came from.

Though I know he wasn’t especially tall, in my memory he is huge. He had thick arms, big hands, and the close-cropped hair of a man who had several children and no time. Caleb (a third grader) wouldn’t have appeared at all unnatural holding a tumbler of scotch in one hand and a cigar in the other as he hooted and hollered recounting a wild tale about pheasant hunting with his daddy. He had a toothy grin and his round, freckled cheeks framed pale-blue eyes that twinkled with warmth and mischief. He was a good ol’ boy before either of us knew what a good ol’ boy truly was. I can picture him vividly saying, with a sly wink, “I’m just a good ol’ boy.” I’m almost certain that isn’t a real memory, but I’ve manufactured it because it works so well.

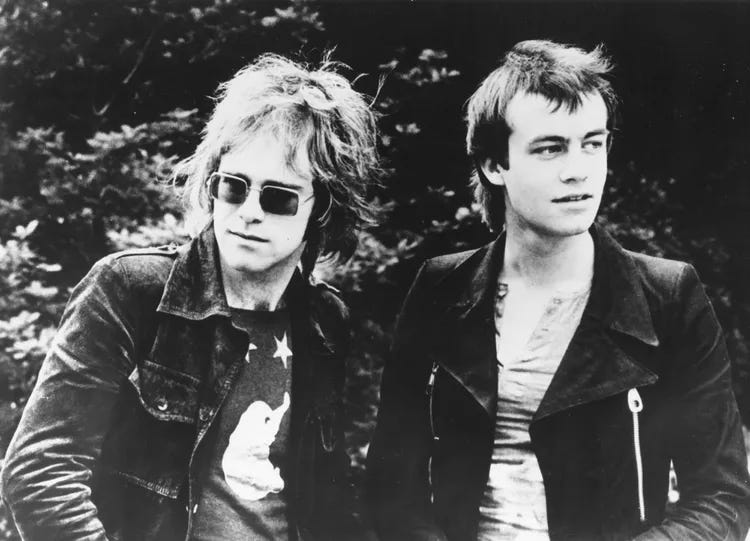

Caleb and his father participated in Civil War reenactments—all the rage in Virginia at the time—as Confederate soldiers. For them, it was nostalgic, even romantic. Recalling the way these two men [sic] spoke about reenacting the American Civil War brings to mind the brilliant Elton John album Tumbleweed Connection. Both John and his songwriting partner, Bernie Taupin, have said they regard this album as among their most lyrically and melodically perfect. It’s quite a statement, and I actually agree. It’s a gorgeous collection of songs, undeniably, and written by two Englishmen who had never set foot in America when they recorded it. It’s explicitly not American—it’s Americana. It’s a fantasy. When I listen to it, I’m transported to a place I would thoroughly love to be, had it ever existed as they’re imagining. The songs’ protagonists sing about fighting for justice and honor, hitching rides on steamboats, falling in love during wartime, and defending the legacy of their families.

I did not grow up with a sense of family legacy, nor a sense of where I came from. Where did I come from? What is a legacy? The remoteness of my family history—my genealogical vacuum—has always induced me to feeling somewhat foreign no matter where I am and intensified my feelings of only-ness as a child despite being a brother, an uncle, and a son. The irony of success in my field as an actor is that, for all the literal fanfare it brings, it creates its own sort of vacuum. Despite being known in some manner by millions, my experience of solitude was only magnified as I matured through my twenties under the specter of celebrity. Have you not heard? Being famous can be so unpleasant!

Having written one-third of this book (and willing to take all the credit), it strikes me that my life experience has been one of spending time between extreme environmental opposites—solitude and celebrity—which have the same internal condition. Quite simply, the feeling of being alone. Imagine, if you will, for a moment: a man nearing forty years old, with a smattering of gray in his beard and upon his temple, with a wife and two children, and who, after nearly twenty years in the spotlight, is attempting to describe (at book length) his experience of isolation growing up without using the word “lonely.” Why would he do that? What could warrant such mental gymnastics? Why would he, even for a moment, second-guess himself in the use of such a universally employed word to describe a universal experience? What could possibly exert such a malevolent force upon his psyche that he would, in his loneliness, be barred from even naming it?

Yes, I was a lonely boy. As a man, this sensation deepened. I hadn’t created my own loneliness as a child, but it had become my responsibility to acknowledge, understand, and break the cycle as an adult. I’m still learning how to do this. What I offer now—after having dragged you through the mud with me—is the light at the end of the tunnel, one that I couldn’t have imagined while I was growing up.

There are two lights, actually. One is standing right in front of me. My wife and I have a four-year-old son, whose bed I am writing from because every other room in our four-bedroom Brooklyn apartment is occupied. On this bright and frozen Sunday afternoon in February, I couldn’t be alone if I tried. My sixteen-year-old stepson—the other of the two lights—is in his room next door, where I can only assume he is bathing in the designer cologne he has recently purchased for himself. (If you’re wondering, yes, providing guidance and watching him traverse his own adolescence over the last few years—the exact same years I’ve been cohosting Podcrushed—has been poignant, serendipitous, and a tad psychedelic.) Across the hall, my wife is answering emails, like any professional on a Sunday, as she sits in our bed. And my mother is in the office that acts as our guest room, where she has been reading Winnie-the-Pooh to the four-year-old who has now come to find me.

He is standing at his dresser in a plain T-shirt and dark sweatpants with a white drawstring that he wisely refers to as “teenager pants” because he sees his beloved big brother wear pants like these almost every day (with slip-on sandals, no matter the weather). His little back is turned to me as he opens every drawer. Deciding he hasn’t found what he needs, he closes every drawer, and every time he shuts one, he mutters, “Shoot.”

This is the point of the exercise. He’s not really looking for anything. He wants to perform for himself (and me) the act of being a little bit frustrated and being able to express it. When he does this, he says it exactly as my mother does. It’s an uncanny resemblance. No one else in our family says “shoot.” What’s more, he doesn’t do this through the mysterious, generational osmosis that can happen within a family, where a child exhibits behaviors of a parent or grandparent or uncle or aunt without knowing it, or possibly without ever having witnessed it. What my son is doing is intentional. He is consciously repeating what he sees my mother do all the time, because he sees her all the time.

I have endured long periods of estrangement from both of my parents, just as they did theirs, and for reasons that might be superficially various but which are ultimately the same. We’ve not known love well: how to use it or what it is for. We’ve not known that it is a verb, or how to use it as a tool. Until I entered my thirties—my thirties!—I didn’t know that it required attentive cultivation. Now that my four-year-old son has taken his pants off and his tiny bare bum is squarely facing me (still wearing his shirt), I can smile and appreciate that the family I belong to is finally learning something about love and how to make it work. I’m learning how to break the cycle.

When my wife was pregnant with our first child, we lost it very early on. We tried and got pregnant again. We made it a bit further, but the first time I was ever in an obstetrics office for a sonogram to see my child in utero, there was no heartbeat. This was our second loss together, a time when it did not feel as though the cycle would break. My wife and I neared separation, as many do after losses like that, largely because we felt so isolated in a culture that doesn’t talk much about these things or know how to support those going through it. Seeing our still baby in that tripped-out black-and-white sono-imagery is a dreadful memory I can’t shake every time we go for a sonogram now. As of this writing, my wife is pregnant, and we have identical twins on the way.

They will make it four lights, soon. Today marks the conclusion of the first trimester. This is when, in America, it is finally advisable to tell people about a pregnancy because the first trimester is reportedly where the most miscarriages happen. Elsewhere, like in Puerto Rico, where Nava grew up, people tell everyone as soon as they can, so friends and family can pray for the little ones on their way—to encourage them. Nava told me this weeks ago when I shared our news with some hesitation. She also reminded me of something Dr. Laurie Santos (actual happiness expert) said on Podcrushed when we were interviewing her: in any kind of loss, your grief is never abated, prevented, or reduced by not allowing yourself joy and excitement while you actually have the thing. So enjoy it.

Speaking of things, my son has left the room and returned triumphantly, now wearing brightly colored Hot Wheels underwear patterned with neon-red race cars and a long-sleeve Nike jersey that says in large and patronizing block letters: “WATCH AND LEARN.” My wife would never purchase clothing so full of microfiber plastics. I know this is my mom’s doing—a gift from Gaga. My son pats the crotch of his underwear and says with wonder, “I found where to put my penis.”

I’m glad it’s easy now. That journey will only become more difficult, son.

Before I can say anything, he bounds out of the room and down the hall where I can hear my mother shuffling to meet him. She’s currently losing her little sister, my aunt, to dementia—a slow and painful loss by degrees. My mother has been the oldest of her generation for several years now. It admittedly doesn’t take much to bring her to tears these days, but when she first saw pictures of our twins in utero, she wept and noted poignantly, “My life started with twins, and it’s going to end with twins.”

Not all cycles need to be broken.

Excerpted from Crushmore: Essays on Love, Loss, and Coming-of-Age by Penn Badgley, Sophie Ansari, and Nava Kavelin.

Penn Badgley is an actor, writer, musician, and co-host of the hit podcast Podcrushed. Although many know him fromYou and Gossip Girl, Penn’s deeper creative focus centers on the interior world—how identity forms, how we heal, and how the experiences of youth ripple through the rest of our lives.

On Podcrushed, Penn joins Sophie Ansari and Nava Kavelin in crafting a thoughtful, disarming space where guests revisit the moments that shaped them. Together, they explore the tenderness and turbulence of growing up, inviting listeners into stories of early longing, humiliation, hope, and discovery.

With Crushmore, the trio shift their gaze inward, offering their own coming-of-age stories for the first time. Told with warmth, self-awareness, and a generous dose of humor, Crushmore follows the winding path from youth into adulthood—reminding us we can find healing—and even inspiration—from our awkward adolescent selves long after we thought we left them behind.