Ryan Holiday Talks Justice and Belonging

On the Soul Boom podcast AND in this week's guest essay

Salutations, Soulful Stoics!

Here’s a little thought experiment: What does it actually mean to do the right thing—especially in a world that makes shortcuts, self-interest, and “looking out for number one” seem like the easier option?

That’s the heartbeat of this week’s Soul Boom episode. Ryan Holiday—the mind behind The Daily Stoic and one of the clearest public voices for ancient wisdom today—sits down with Rainn for a conversation that cuts through the noise of our modern lives.

They dig into a radical idea: personal growth is not enough. (Yep, your meditation app and gratitude journal are great, but without justice, they don’t get us all the way there.) The Stoics insisted that every virtue—wisdom, discipline, even courage—rests on a foundation of justice. Take that away and the whole building collapses. Which might explain why so much of our current world order feels like it’s wobbling.

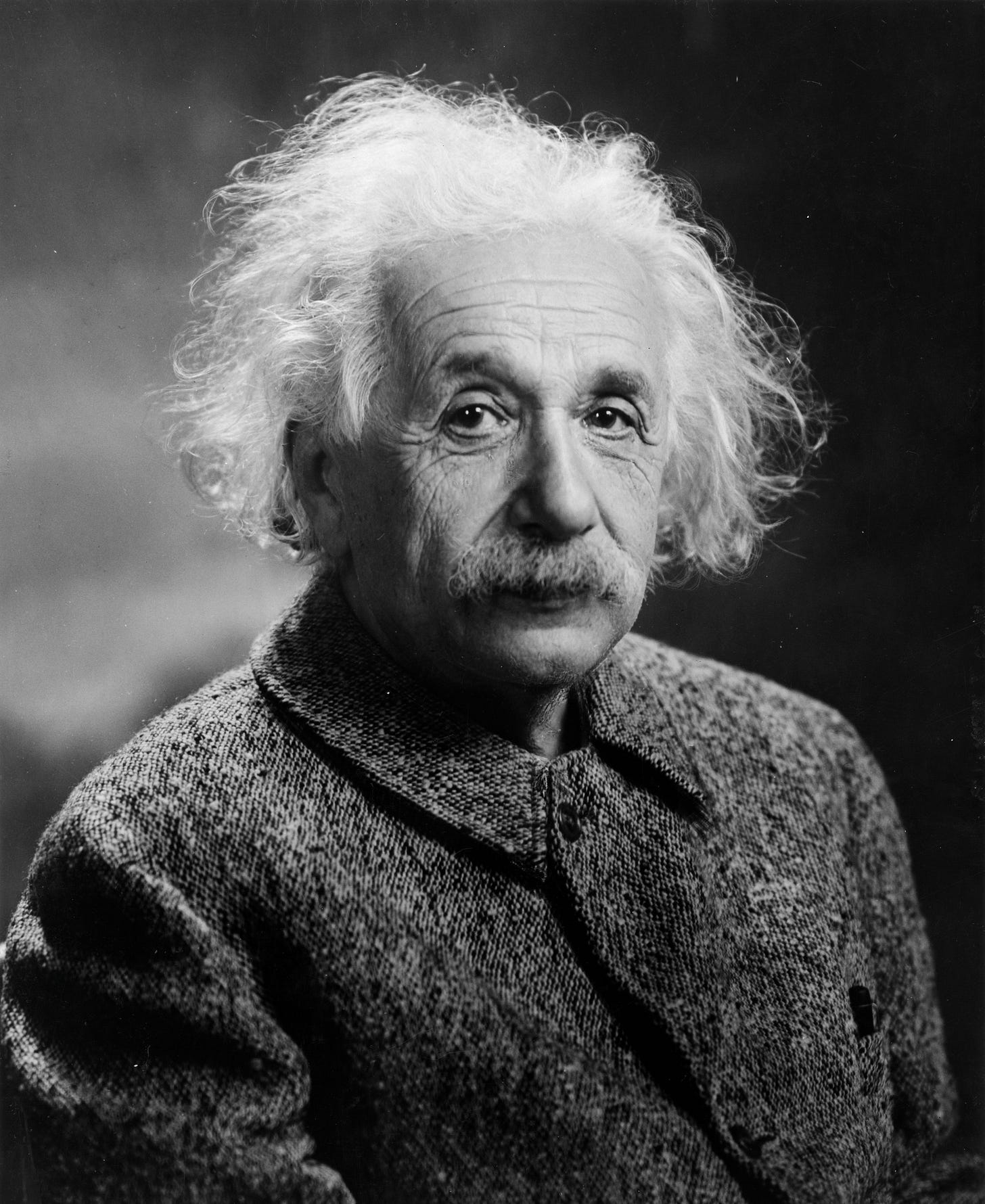

To keep the conversation going, we’re sharing a post from Ryan’s website in which he references ideas presented in his book, Right Thing, Right Now — the third in his Stoic Virtues series, and maybe the most urgent. In it, he draws on Einstein, Baldwin, Gandhi, Marcus Aurelius, and even William Shatner (yes, Captain Kirk himself) to remind us of a timeless truth: we belong to each other. When we forget that, injustice takes root and we’re all at risk.

Stay steady,

The Soul Boom Team

This Is What You Belong To

by Ryan Holiday

In 1950, a man grieving his young son who had just died of polio got a letter from Albert Einstein. Now, one might think that as a man of science, Einstein would have had a rather resigned view of the tragic nature of the human condition.

We’re born. We’re buffeted by forces beyond our control, beyond our comprehension, and then we die. Often for no reason, leaving profound suffering in its wake.

Given the immensity of the events of the middle of the twentieth century—the Holocaust and the violence of the atomic age—it was quite reasonable that Einstein might be inured to the loss of a single child to whom he had no relation.

Instead, Einstein’s letter was one of profound and philosophic condolence.

“A human being,” he wrote, “is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.”

Einstein was expressing one of the few things that physics and philosophers and priests seem to agree on: That everything and everyone is far more connected than we are prone to think. We shared an animating force, an energy, a unity that no matter what happens or how different things seem is always there. Even in our suffering, in our grief, we are tapping into something eternal and vast, something that makes us realize we are very much not alone.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world,” James Baldwin wrote, “and then you read.” It was books, history, philosophy, Baldwin said, that taught him that “the things that tormented me were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.”

We are all one. It’s so easy to forget it, but it’s true.

The virtue of justice–what my new book Right Thing, Right Now is all about–is this idea that because of interconnectedness and interrelatedness, we have an obligation. Stoicism is not lone-wolfness. It’s the understanding that we are one single organism and that the fate of one is the fate of all.

As I wrote in Stillness is the Key, no one has felt this more profoundly than the astronauts who had the unique experience of seeing the Earth from space. Whether they were American or Russian or Chinese, they were all overwhelmed by what has been called the “overview effect,” an instantaneous global consciousness, an inescapable sense that everyone is in the same boat, no matter where they live or what they believe.

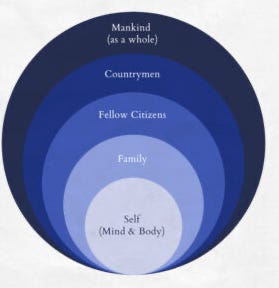

What they experienced looking at the “Blue Marble” that is our planet was the exact thing that Hierocles, the 2nd century Stoic, was trying to teach people about two thousand years ago. Yes, we naturally think of ourselves and the people we love first, but with work, we can expand that circle of concern larger and larger until we see everything that is alive as one enormous organism. Astronauts experience the exact same thing that Gandhi, who never even flew in a plane, never saw humanity from above more than a few stories up in a building, called the great oneness.

Realizing this, letting it wash over us, sitting in awe of it—it’s more than just humbling. It also makes us more generous, more courageous, more committed to what’s right. It makes us less concerned with petty nonsense, with meaningless distinctions, with grudges or our own pain.

It’s euphoric. It can also be existentially devastating.

The actor William Shatner, after a lifetime of exploring space on film, finally visited the cosmos at age ninety. He thought he’d marvel at the beauty of all that he beheld. Instead, looking at the Earth from afar, all he felt was sadness.

Because, he realized, everything that mattered was down there on Earth and everyone was taking it for granted. They were destroying this thing of beauty, abusing it, stealing it from generations unborn.

The garment of interdependence, the great bundle of humanity that Frances Ellen Watkins Harper spoke of, it’s real. But what kind of shape is it in these days? The environment is reeling. Billions live in poverty. Millions perish of totally preventable causes. Injustice tears at the fabric that binds us together.

How long can it go unchecked before everything comes apart?

I am convinced that people are much better off when their whole city is flourishing than when certain citizens prosper but the community has gone off course. When a man is doing well for himself but his country is falling to pieces, he goes to pieces along with it, but a struggling individual has much better hopes if his country is thriving.

Is that the lament of a modern politician? The manifesto of some early-twentieth-century socialist revolutionary?

No, it’s Pericles in 431 BC.

The whole point of government and the social contract is built around this idea. All government, it was said by one of the Founders, have as its sole goal the common welfare.

What good is our success if it comes at the expense of others? How safe are we if our safety leaves others vulnerable? What good are we if we can’t help others? We are all bound up in this thing called life together. We share this planet together. When we forget that, or lose track of how our own actions affect others, that’s when injustice flourishes.

Marcus Aurelius’s line that “what’s bad for the hive is bad for the bee” could just as easily be a quip in an upcoming political debate as it could be a New York Times op ed. It’s something that he needed constant reminders of, just as we do. He strove to see the world “as a living being—one nature and soul . . . [where] everything feeds into that single experience, moves with a single motion. And how everything helps produce everything else. Spun and woven together.” Did his policies and decisions always reflect that? No. And his biggest failings—the persecution of the Christians by the Romans at that time—are a reflection of what happens when we lose track of that ultimate north star.

“I am not conscious of a single experience throughout my three month stay in England and Europe,” Gandhi observed after one of his visits, “that made me feel that after all East is East and West is West. On the contrary, I have been convinced more than ever that human nature is much the same, no matter what clime it flourishes.”

This was why he couldn’t hate. Why he couldn’t turn his back. Why he dreamed of a better world with fewer divisions, where problems were never solved by violence or domination. “Life will not be a pyramid with an apex sustained by the bottom,” he explained, sounding like Hierocles. “But it will be an oceanic circle whose centre will be the individual always ready to perish for the village, the latter ready to perish for the circle of villages, till at last the whole becomes one life composed of individuals, never aggressive in their arrogance but ever humble, sharing the majesty of the oceanic circle of which they are integral units.”

This is what the last years of his life were dedicated to, why he was willing to die not just for independence but for equality for the untouchables and for Muslim and Hindu peace. “I am a Muslim,” he said, “a Hindu, a Buddhist, a Christian, a Jew, a Parsi.”

And so are you. We all are.

We are one and the same. All mortal. All flawed. All gifted with incredible potential. All deserving of justice and respect and dignity. All unique individuals and yet an inseparable part of humanity, of the past, present, and future.

Truman kept a line from a Milton poem in his wallet that read simply:

The parliament of Man, the federation of the world.

That’s what we belong to. That’s what we must protect.

From Ryan Holiday’s Right Thing, Right Now: Good Values. Good Character. Good Deeds. Ryan Holiday is a writer, thinker, and modern-day interpreter of Stoic philosophy. The author of more than a dozen books—including the New York Times bestsellers The Obstacle Is the Way, Ego Is the Enemy, and Discipline Is Destiny—his work has sold over 10 million copies and shaped leaders across fields from sports to politics to business. Through The Daily Stoic, his hugely popular newsletter and podcast, Ryan brings ancient wisdom into daily practice, helping millions navigate life’s challenges with resilience, integrity, and perspective. He lives outside Austin, Texas, where he runs The Painted Porch bookstore, raises cattle, and continues to explore how timeless principles can guide us in a turbulent modern world.

I'm really looking forward to listening to this podcast. I do struggle with the concept that all of us are one. There is so much evil in the world, and so much sadness when people we love are taken from us. Lately I've tried to think of us all as leaves on one huge tree. We age and fall off in season, and when we fall, we are absorbed into the soil and become nutrients for new life. Nothing in nature is wasted. So perhaps those "evil elements," individuals who seem bent on destroying others, are "leaves" that have been infested with some sort of invasive parasite. And those "leaves" who fall while still in their youth are struck by an early frost. This picture helps me grasp the concept of "all as one." After all, whenever I go out into nature, I feel more a part of everything, and I also feel ageless.

“Do not pity the dead, Harry. Pity the living and, above all, those who live without love” (spirit of school headmaster Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2).

For some of us, the greatest gift life offers is that someday, preferably sooner rather than later, we get to die — and not have to repeat the suffering. But when suicide is simply not an option, it basically means there’s little hope of receiving an early reprieve from their literal life sentence.

And, of course, reincarnation — especially back into the average bitter Earthly human existence an indefinite number of times, the repetition of mostly unhappiness — would be the ultimate unthinkable Hell. Ergo, the following poem:

__

I awoke from another very bad dream, yet another horrid reincarnation nightmare

where having blessedly died I’m still bullied towards rebirth back into human form

despite my pleas I be allowed to rest in permanent peace.

My bed wet from sweat, I futilely try to convince my own autistic brain

I want to live, the same traumatized dysthymic brain displacing me

from the functional world.

.

Within my nightmare a mob encircles me and insists that life, including mine,

is a blessing.

I ask them for the blessed purpose of my continuance. I insist

upon a practical purpose!

Give me a real purpose, I cry out, and it’s not enough simply to live

nor that it’s a beautiful sunny day with colorful fragrant flowers!

.

I’m tormented hourly by my desire for emotional, material and creative gain

that ultimately matters naught, I explain. My own mind brutalizes me like it has

a sadistic mind of its own.

I must have a progressive reason for this harsh endurance!

Bewildered they warn that one day on my death bed I’ll regret my ingratitude

and that I’m about to lose my life.

I counter that I cannot mourn the loss of something I never really had

so I’m unlikely to dread parting from it.

.

Frustrated they say that moments from death I’ll clamor and claw for life

like a bridge jumper instinctively flailing his limbs as though to grasp at something

anything that may delay his imminent thrust into the eternal abyss.

How can I in good conscience morosely hate my life

while many who love theirs lose it so soon? they ask.

Angry I reply that people bewail the ‘unfair’ untimely deaths of the young who’ve received early reprieve

from their life sentence, people who must remain behind corporeally confined

yet do their utmost to complete their entire life sentence — even more if they could!

.

The vexed mob then curse me with envy for rejecting what they’d kill for — continued life through unending rebirth.

“Then why don’t you just kill yourself?” they yell,

to which I retort “I would if I could. My life sentence is made all the more oppressive by my inability to take my own life.”

“Then we’ll do it for you.” As their circle closes on me, I wake up.

.

Could there be people who immensely suffer yet convince themselves

they sincerely want to live when in fact

they don’t want to die, so greatly they fear Death’s unknown?

No one should ever have to repeat and suffer again a single second of sorrow that passes.

Nay, I will engage and embrace the dying of my blight!

_____

P.S. By definition, I’m actually not suicidal.