The Weird, Wonderful World of Reggie Watts

On the podcast with Rainn PLUS an excerpt from his memoir

Greetings and Soulutations!

This week on the Soul Boom Dispatch, we’re thrilled to welcome the visionary Reggie Watts.

We think you’ll enjoy this wide ranging convo touching on some big themes. A lot of stuff came up. Actually, Rainn and Reggie had such a rich, wide-ranging conversation that we’re seeing double.

Double the trouble.

Double the delight.

Double the dollop of soulful musings on creativity, identity, belonging, and what it means to be human in a very strange world.

That’s our way of saying: it’s a two-parter (you can look forward to the second part coming out next week).

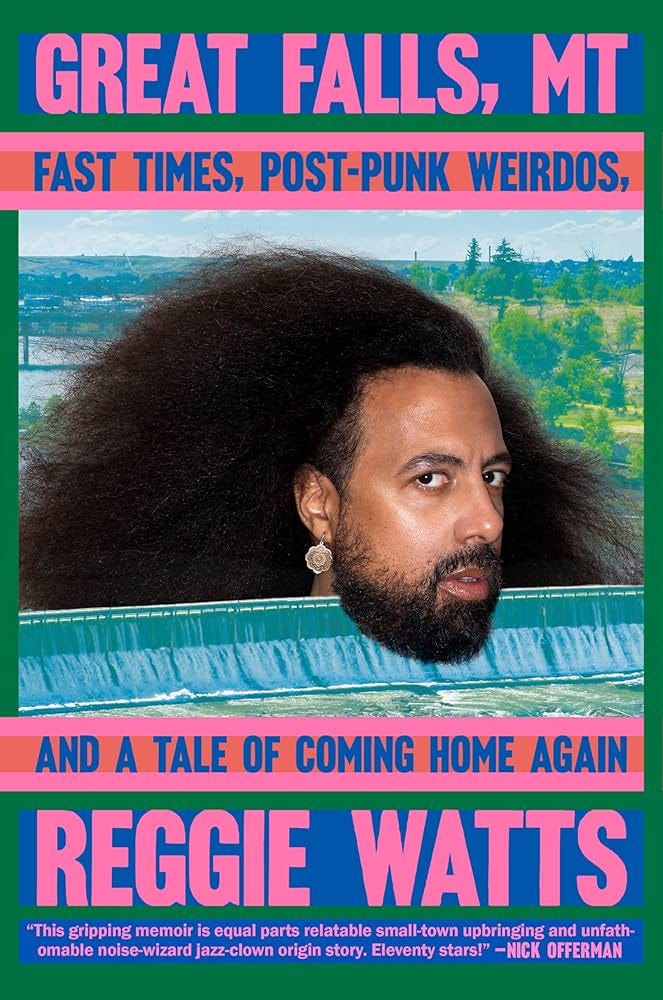

Reggie brings both a tender heart and a brilliant, searching mind to everything he does. In preparing for this conversation, we spent time with his moving memoir, Great Falls, MT—and suddenly, a lot clicked into place. You watch and listen to Reggie and find yourself wondering: How can this person even exist? Reading his backstory, it all starts to make sense. (It also happens to be a wise, riveting book—highly recommended.)

As Reggie explains in the memoir, he comes from a truly hybrid experience. His father was an African American U.S. Air Force serviceman, and his mother was a white French woman he met while stationed in Germany. Reggie spent his early childhood moving through Europe—including time in Madrid—before eventually settling in the United States. Long before he ever set foot in Montana, he was already living as something of a world citizen, absorbing difference, multiplicity, and contradiction as part of everyday life—languages overlapping, cultures colliding, identities coexisting.

In his book, he writes about this early sense of cosmopolitanness in his distinctive voice:

For reasons I still don’t understand, I was born without citizenship to any country. Literally. I didn’t have American citizenship, or French, or German. I was legally a Nothing. That’s not something I technically understood at the time, of course—I was too young—but somehow, on some level, I absorbed the reality of my jumbled identity, and I embraced it. I was the consummate outsider. A cosmopolitan who lived in awe of the cool, colorful world that surrounded me.

Reggie describes afternoons in Madrid with his father—watching the city move by taking in the people, the languages, the sheer variety of human expression:

Tall and short, heavy and thin, light-skinned and dark. Blue eyes, hazel eyes, blond and brunette. Each person completely unique… And their voices. So many voices! Madrid was a truly international city, and I found myself engulfed by more languages than I ever knew existed. I let the sounds wash over me… like a strange sort of music.

What’s striking, reading about Reggie’s early life, is realizing that the seeds of his entire oeuvre were planted in childhood. If you’ve ever seen a Reggie Watts performance, you’ve probably watched him slip effortlessly into different accents, characters, and sometimes into pure, glorious gibberish. That wasn’t a party trick that arrived later in life. You can see the source code for that code switching forming early on: a young, wildly curious mind steeped in multiple languages, cultures, and ways of being. When your neurons are marinating in that kind of diversity from the jump, creativity doesn’t just develop—it multiplies exponentially. Your neural wiring bends toward play, pattern, and possibility. No surprise, then, that Reggie would grow up to become a visionary performer whose work defies categories and genres—yet always radiates absurdity, wonder, and a deep, disarming kindness—often all at once.

But we digress. Before there was the Reggie Watts of today, there was a much smaller Reggie, just beginning to make sense of the world.

That little Reggie traveled with his parents across continents, leaving behind the urbane streets of Madrid for a very different landscape: “The Big Sky Country” of a landlocked northwestern state in the US. Our excerpt this week begins just as he’s settling into his new home…

MY OWN PRIVATE MONTANA

By Reggie Watts

It was a hazy summer afternoon when I finally worked up the courage. I had been staring out our big living room window at the house across the street for what felt like forever.

Once we moved into our new house, it hadn’t taken long to figure out if any kids lived across the street. Two boys—brothers—right around my age. Just normal, average Montana kids. Brown hair, brown eyes, easy laughs whenever they played outside together. But I was a normal Montana kid now too, wasn’t I? Brown hair, brown eyes, an easy laugh when I played outside. And brown skin, also that.

But after my experience with the other kids at my day care, I became a little hesitant to make other friends in my neighborhood. It had been months since we got settled, and I still hadn’t even introduced myself. I wasn’t typically shy, wasn’t naturally uncomfortable around other people. I just wasn’t sure what to say. I worried that the jumble of languages in my mind would confuse kids, keep them away. Maybe once I learned some bigger words in English, became more comfortable speaking the local language, maybe then I could walk around to the other houses to meet some people.

Then something had happened. I had gone from being a nothing to being a something. I had gotten my American citizenship.

Once we’d gotten settled in Great Falls, my mom had made it her mission to get me my citizenship. She had no interest in it for herself. Even though she was married to an American service member and could’ve easily qualified, she refused to get anything beyond permanent residency. It was a matter of principle, she said. She was French to her core—her spirit was French, her identity was French—fiery, strong, willful—and she’d always be French, no matter where she lived. She would never change that.

Maybe that was why she was so insistent on getting me my American citizenship as soon as we got to the States. She wanted me to know that whatever language—or languages—I spoke, whatever color my skin, I belonged in this country. This was my home, this was my birthright, and no one could take that away.

The morning I took my oath at the town courthouse, I started to understand just what it meant to be a citizen, to have a nation of my own. My mom dressed me in a nice sweater. I had memorized the few facts I thought I needed to know. The old white guys who founded the country declared independence on July 4, 1776. I had that one down pat.

And it was another old white guy who administered the Pledge of Allegiance that day—Judge Carter, a man who’d taken a liking to me and my family, who’d helped my very insistent, very strong mother expedite the citizenship process.

But when I looked around the room at the courthouse, I realized that, other than the judge, most of the other people there looked more like me. Not necessarily Black, though some were. But different shades of brown, their hair different textures, their noses different shapes, their accents something other than the usual Montana drawl. Once we took our oath, all of us would be just as American as Judge Carter or the kids on my block or anyone else in Great Falls.

Except of course my mom—because to hell with that, she was French.

With that newfound confidence, I took a deep breath, walked out our front door, and headed across the street to see if my neighbors could come out to play.

Their house looked like ours—most of the houses in our neighborhood did. But there was something a little shabbier about their place. The grass was long and shaggy, the hedges hadn’t been trimmed. The driveway was the only one in the neighborhood that wasn’t paved. It was gravel, and I liked to think of their house as the Fred Flintstone House.

I stepped onto their unfinished drive, and my feet made a soft crunching sound as I slowly approached their door. The curtains of their big living room window were pulled closed, but I had seen the boys playing on the porch earlier, so I knew they were home.

I pushed the doorbell and waited. Nothing. Maybe the doorbell was broken. I knocked on the aluminum frame of the screen door, and after a few seconds I heard heavy footsteps inside.

The door opened and a big man I recognized as the boys’ father stood there looking down at me. He was wearing blue jeans and an old white undershirt. I was wearing suspenders. I wore a lot of suspenders back then. Suspenders and sweaters—that was my look.

“Hi there,” I said in my meticulously rehearsed English. “My name is Reggie. I live across the street. Can the boys who live here come out and play with me?”

The big man frowned.

I don’t remember exactly what he said after that. I just remember that he used a bunch of words I didn’t know and they didn’t sound very nice—and one of those words started with an n. Seconds later I was crying and running back across the street. Crying, I’m crying now, so this is what pain feels like, I really don’t like it. My mom had always told me to look both ways before crossing, but I didn’t care. I just wanted to go home.

As soon as she heard my cries, my mother rushed out of her red kitchen and into our living room.

“Reggie, qu’est-ce qui se passe?”

I told her the word our neighbor had called me.

I’d seen my mom angry before, but I’d never seen her like this. Her hazel eyes flashed a brighter shade of red than her hair. When she had been spat at in Cleveland, she had endured it with strong, quiet dignity. But that had happened to her. This was her son.

She grabbed my arm and marched me right back across the street. I noticed she didn’t look both ways either. She pounded on the door, and the big man in the old white undershirt opened it with a smug look on his face. That didn’t last long.

“Now you listen to me, you piece of white trash! Zis is just a little boy, and you talk to him zat way? Huh? Are you crazy? I’m telling you zis right now—if you ever mess with zis kid again, I will come for you. I swear it! I will come for you!”

I had no idea my mom knew that much English.

Technically, she wasn’t that physically imposing. A little over five feet tall, maybe a foot taller than I was. But you get a small bundle of pure redheaded French rage coming right at your face, and let’s see how well you hold up. This dude didn’t say a word. Just slammed the door.

So my mom called the cops. A few minutes later lights were flashing across the street as a couple of cops—both white, of course—knocked on my neighbor’s door and had their own conversation with the man in the old white undershirt. Probably a little more polite than my mom, but with the same basic message: he’d better leave me alone from here on out.

I couldn’t help wondering how many other kids in our neighborhood had seen us stomping back and forth across that street. Had noticed the police reaming our neighbor out moments later. What would they think of me? Would anyone want to be my friend now?

Later that night, my dad came home from work. My mom told him what had happened. He shook his head and sighed. It was like all his fears about moving back to America were coming true.

“This won’t be the last time, Reg,” he said. “You’re gonna have to learn how to stand up for yourself. Some white kid calls you the n-word, you call him a redneck honky. Some white kid hits you, you hit them back. Harder, if you can. That’s life. You better get used to it.”

Now, I was just a little boy. My dad knew that. I don’t think he expected me to defend myself against a grown man five times my size. But he felt like he had to prepare me for the same harsh realities he had dealt with growing up.

Then there was my mom. She was a natural fighter.

“Si quelqu’un te dérange, dis-moi,” she whispered to me. “Je m’en occuperai d’eux.”

If someone gives you trouble, you tell me. I’ll take care of them.

But I knew I needed to find my own path—the same way I needed to find my own identity.

My dad was right. I did get called the n-word again. Not a lot, but it happened. To be clear, Montana isn’t the uncivilized backwater so many Americans assume it to be. Are there racists? Ignorant people who say and do stupid things? People who take their frustration out on others, even kids? Absolutely—just like everywhere else.

But I had zero interest in fighting. Zero interest in telling someone off or punching someone with a judo chop. I hated confrontation. It’s just not who I am.

Instead, I decided to transcend my differences with others. I decided to make people like me, whether they wanted to or not.

I invented my very first social hack.

I stepped to the front of the living room at the old lady’s day care down the street, right next to the big TV. Except this time, no one was holding my hand. I was on my own.

Maybe Great Falls was different from Madrid. Maybe there wasn’t the culture or the architecture or the languages. But even at that young age, I sensed that with its wide plains and sprawling new neighborhoods, Montana possessed a kind of openness—a kind of possibility. People tended to keep to themselves, but that also allowed a certain freedom. A chance to be whatever you wanted to be.

Moving to a strange new country, starting with a clean slate—that didn’t have to be a bad thing. Sure, my life was full of uncertainty. But if I looked at it the right way, that uncertainty could be exciting. An adventure. Fun.

The other kids at the day care were playing with each other, ignoring me. But I was about to change that.

“Hey, all you kids!” I shouted, accent and all. “Vous aimez danser? Then look at me!”

And then I started to dance.

In real life, it was a funny little jig—shuffling my feet, wiggling my hips, pointing my fingers in the air like a preschool John Travolta.

But in my mind?

I was living free. All the lines broke down. All the barriers dissolved. My self-awareness lifted, my mind relaxed, and I just was.

Most important of all, the other kids loved it. They loved me. We shared a frequency. They were clapping, laughing—not at me, not even with me, but simply everywhere.

After a couple minutes of nonstop jiggling and gyrating, they weren’t calling me “new kid.” They were chanting my name.

If other people thought I was different, I wasn’t going to fight it. I wasn’t going to prove them wrong. I was going to prove them right—by being the biggest, craziest, funniest “different” they’d ever seen.

I was gonna be the biggest oddball in the history of Great Falls, MT.

Now… I just needed to figure out what exactly that meant.

Excerpted from Great Falls, MT: Fast Times, Post-Punk Weirdos, and a Tale of Coming Home Again by Reggie Watts.

Reggie Watts is an internationally renowned musician, comedian, and writer. He starred as the bandleader on CBS’s The Late Late Show with James Corden and on IFC’s Comedy Bang! Bang!. Using nothing but his voice, looping pedals, and a vast imagination, Reggie blurs the lines between music and comedy. His work spans multiple specials and appearances across platforms including Comedy Central and Netflix.