The Work That Reconnects

Abby Reyes on Joanna Macy’s legacy

Hey fellow travelers,

A few weeks ago, the world lost Joanna Macy. For the uninitiated, she was a renowned writer, teacher, scholar of Buddhism, systems thinking, and deep ecology. For six decades, Joanna was a luminous voice for peace, justice, and ecology, weaving together rigorous scholarship with the lived wisdom of activism. A spiritual grandmother to a whole generation of climate and justice seekers. Her death rang like a bell—reverberating through the movements she helped midwife, and through the lives of so many she touched.

In reflecting on her rich legacy, we realized we know someone who knew Joanna well. Our friend Abby Reyes. Abby is a climate justice leader, lawyer, and author whose pursuits are driven by a deep sense of spirituality, love of humanity and ecology. She’s someone who has walked shoulder-to-shoulder with extraordinary guides—people like Ram Dass, Thich Nhat Hanh, and Joanna Macy herself. People who taught her and countless others how to be of service and stay present when everything in you wants to bolt.

And Abby has carried those teachings into her own life in the hardest way imaginable. In 1999, she lost her partner, Terence Unity Freitas, and two dear friends—land rights advocates murdered in Colombia while standing with Indigenous communities. Her recently released book, Truth Demands: A Memoir of Murder, Oil Wars, and the Rise of Climate Justice, is the story of what it means to face that kind of grief and still choose love, still choose justice, still choose life.

So we asked Abby to write about it: how her teachers shaped her, how their wisdom sustained her through loss, and how their example continues to shape the movements she’s part of. The essay she gave us is about stepping out of the “spiritual closet,” about carrying forward the torch handed down by elders, about the twofold path we’re always circling back to—inner transformation and outer work for a better world.

May Abby’s words remind us that none of us are walking this path alone.

With love,

The Soul Boom Team

P.S. If you’d like to hear more from Abby, check out her superb TEDx talk on the subject of How to Come Home—and also you can find her in Liz Gilbert’s Letters from Love this past Sunday!

The Work That Reconnects

By Abby Reyes

Damp moss padded the banks of the Rappahannock River and mud squished through my toes. I could hear the water but not see it. My hands were wedged into the crook of my friend Kevin’s arm. A bandana covered my eyes. “Look for awe,” we were told. It was everywhere. Every few minutes, Kevin said, “now,” and I opened my eyes to an unfurling fern, a vista of the Blue Ridge mountains, a glistening spider’s web, a towering hemlock.

When the sun grew high, we wandered back to the circle. It was the late 1980s. We were 16-year-old mixed-race brown kids from Virginia, camping with a few dozen mid-career staffers from DC environmental organizations. They brought us to the hills for a weekend training in what would, over time, come to be called “the work that reconnects.”

Our friend John Seed from Australia and his friend Joanna Macy from California had just written a slender missive called Thinking Like a Mountain. John was there, leading us all on how to reconnect. Just as we settled back into the circle, John led us back into the woods. This time, he said, find a living being in the forest, or our imagination, and “get quiet enough to pretend to see the world through their eyes.”

I chose a wolf, or the wolf chose me. That evening, we made masks from string, leaves, ferns and paper. I made a wolf mask. Kevin made a deer. One by one, we spoke through our masks to each other about the business of our lives and the joy in it. It was a council of all beings.

Eventually, our adopted creatures turned to address the humans. They spoke about the dismal state of the world. After their petitions (“please stop killing us”), they had instructions. “Quiet your mind,” they said. “Draw toward stillness not from your despair but from your strength, and listen. Hear in the stillness our parting song. And make our song your own.”

I took it in. The instructions sounded right. I let it shape my vision and change our work. Mind you, at that point, the “work” of our go-getter friends entailed things like running student government, staffing our town’s interfaith thrift shop, protecting local creeks as they flowed into the Chesapeake Bay, and starting paper recycling in Delmarva public schools. It was the earnest work of young people trying to make our small world a better place. But I knew there was more to it. I knew it couldn’t just be about pollution and recycling. I wanted to get to the root, wherever that might be, and work from there.

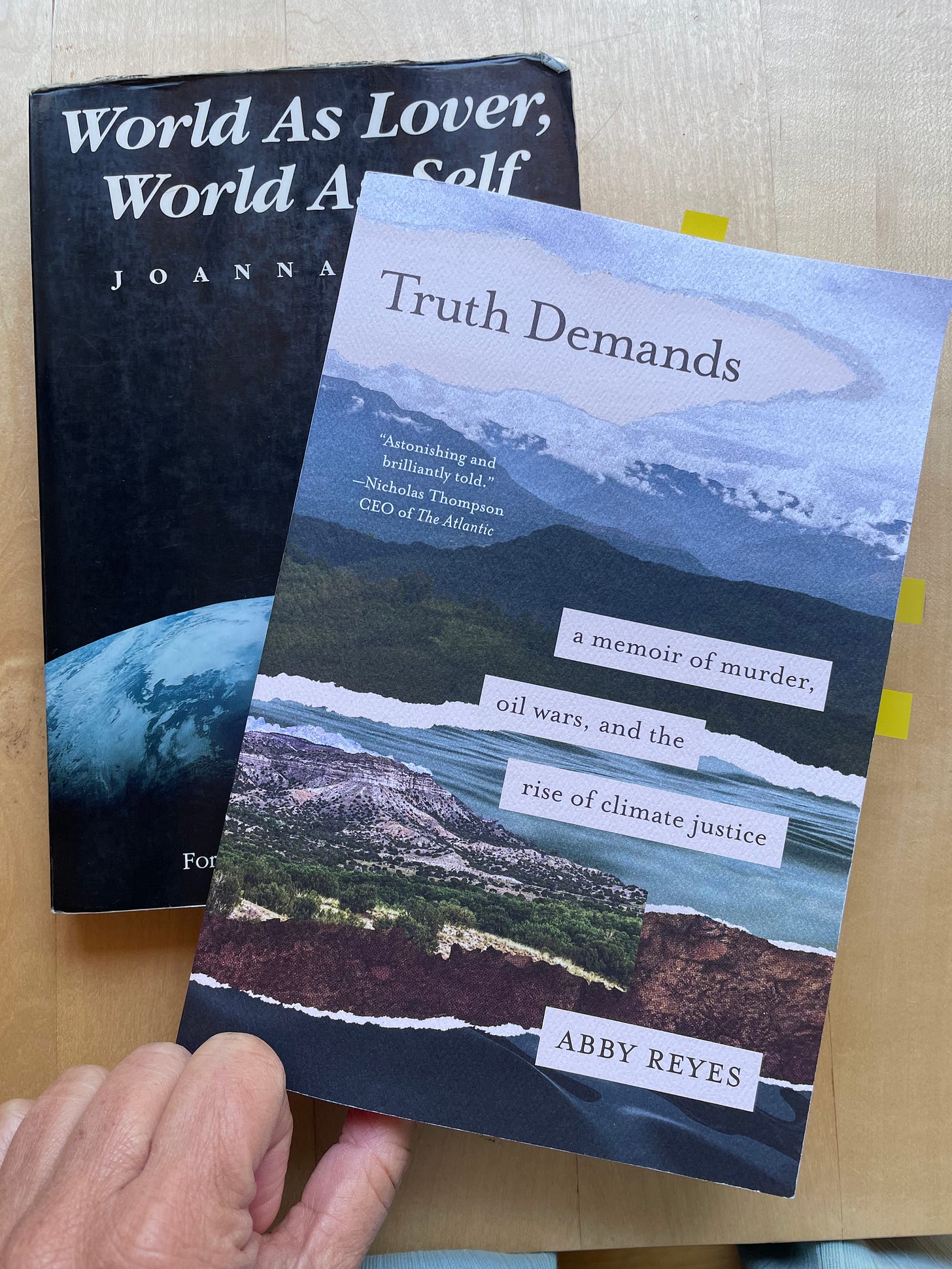

I went west for college. Joanna Macy and her co-author Molly Brown lived there. I buried myself in their book, World As Lover, World As Self. My dog-eared copy is annotated in a teenage girl’s turquoise and fuchsia bubble letters. It was the first time I saw someone name what I felt:

“As a society we are caught between a sense of impending apocalypse and an inability to acknowledge it… It stems from a fear of confronting the despair that lurks subliminally beneath the tenor of life-as-usual. A dread of what is happening to our future stays on the fringes of awareness, too deep to name and too fearsome to face… Until we can grieve for our planet and its future inhabitants, we cannot fully feel or enact our love for them… At the root… lies a dysfunctional notion of the self. It is the notion of the self as an isolated and fragile entity… So long as we see ourselves as essentially separate, competitive, and ego-identified beings, it is difficult to respect the validity of our social despair, deriving as it does from interconnectedness.”

I read it as an invitation to come out of the spiritual closet. Up until then, I had good teachers: Ram Dass, reminding me to be of selfless service; Fran Peavey, teaching me to move like water; Thich Nhat Hanh, guiding me to touch the earth, and Sat Santokh Singh Khalsa, showing me how to find my seat for sitting. But it was Joanna Macy who said the things that were in my heart. She let me know it was okay to be a child of the universe. She also let me know that it was okay, perhaps even necessary, to feel grief about the state of the world. Her writing unleashed me to embody both of these states, and to move through the grief into action.

After college, I kept going west. So far west that I ended up in the east. For two years, I lived on a remote island in the southern Philippines, my father’s homeland, where I worked with fishing and farming communities and learned from Jesuit lawyers the practice of rural environmental legal assistance. Just as I prepared to return to California, one of the Indigenous communities received the proverbial knock on the door from two oil companies.

Shell and Occidental Petroleum wanted to build a gas pipeline through the community’s ancestral fishing grounds. The community did not check their boxes. They did not invite the Shell man any farther into the territory. Instead, they turned to us and asked what they needed to know.

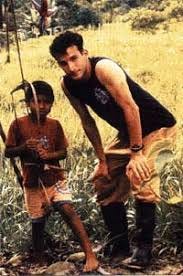

That was my mission when I returned to California–to find out. That’s how I met my counterpart, Terence Unity Freitas. He was working with Pueblo U’wa in Colombia. Both communities were navigating the advances of the very same multinational oil companies.

We compared stories, and in the middle of it, he asked me out on a date. From that moment on, Terry and I were attached at the hip. But it didn’t last long.

On February 25, 1999, during a visit to U’wa territory, he and his colleagues were kidnapped. Eight days later, their bound, hooded, and bullet-riddled bodies were found just across the Venezuelan border. Terry was murdered for his work defending the sacred from oil extraction.

We were 24 and 25 years old. We were mere babes. All these years later, I still find no easy way to tell this story.

What I can say is: I walked into adulthood through the gates of these murders. I had my teacher Ram Dass, who sat with me through the earliest days. And I had the blueprint for moving through grief that Joanna Macy offered in World As Lover, World As Self. But I was still adrift. When we finally met in person, Joanna gave me her new book, Coming Back to Life. I could barely look at it. It hit too close to home.

When the work of the murders’ aftermath did not abate, I realized there was no way back to shore. Instead, I needed to learn how to swim. I swam in any river, lake, pond, or ocean I could find. Navigating the waters taught me how to breathe. The cold shocked me back into the present moment, which is where life needed me to be.

Over time, my colleagues and I began teaching the work that reconnects to student climate action leaders across the University of California system. Instead of the banks of the Rappahannock, our students found awe among the boulders of the Sonoran desert and the cool shade of coastal redwoods. They learned to get quiet enough to seek counsel from all beings, to touch the fear and grief of climate change, and to move through it toward courage, love, and equanimity.

Then I wrote the book that would, eventually, give me some of the answers I needed. Truth Demands is about the murders, oil wars, and the rise of climate justice. It’s also about healing. Joanna Macy was one of my first readers. I had to keep giving her new versions to read because, even as I wrote, the story kept going. Twenty years after the murders, Colombia invited Terry’s mother and me to participate as recognized victims in Case 001 of what they called a transitional justice process.

It was finally, maybe, a forum in which we could find out the root causes of the 1999 murders, and it was not easy. One day, Joanna slipped a puppet onto her hand and had it hand me a scribbled note from Camus’ Resistance, Rebellion, and Death essays. “We have nothing to lose but everything,” it said. “So let’s go ahead.” Go write, she said.

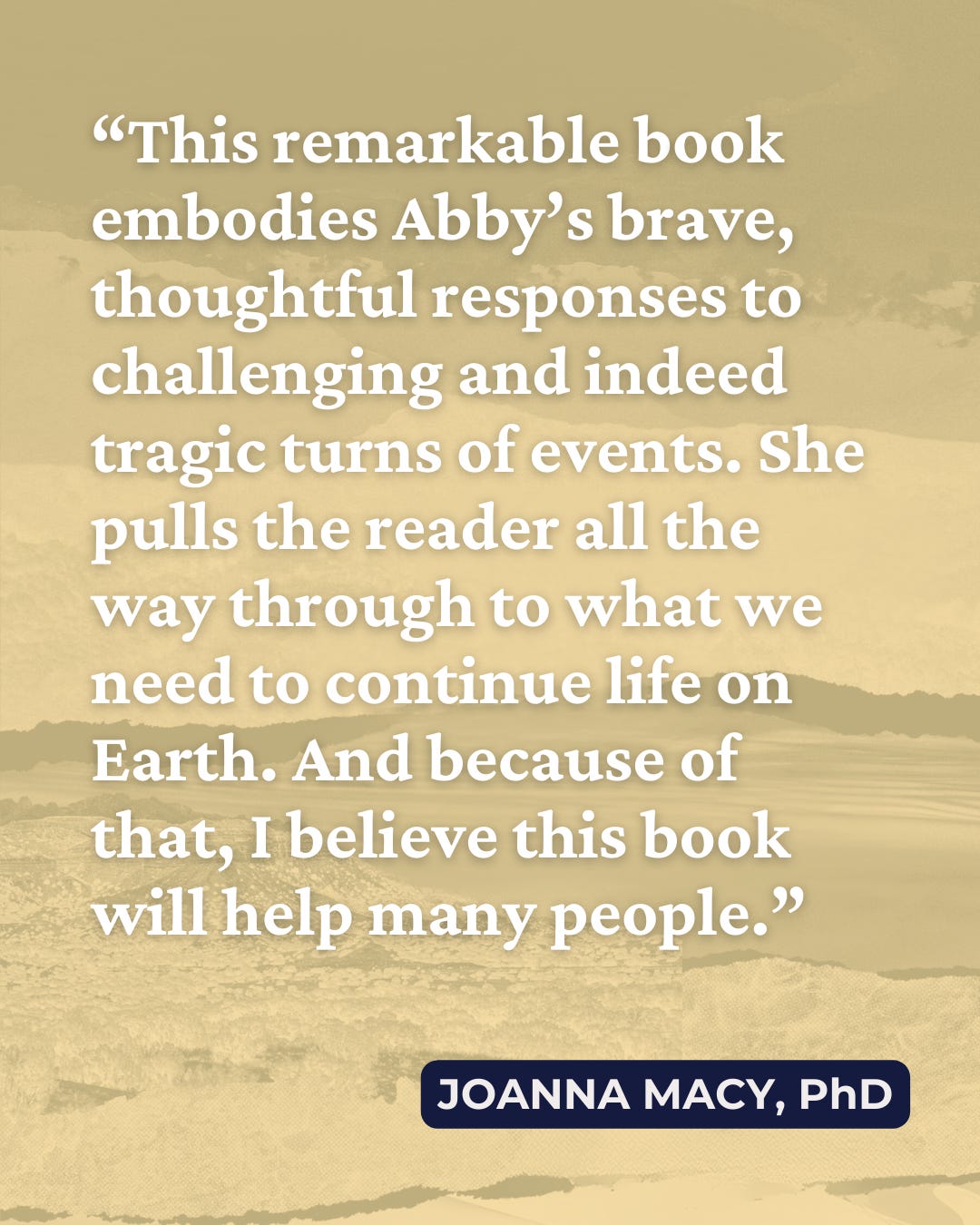

Today, the book features an exhortation from her on the inside cover.

This remarkable book embodies Abby’s brave, thoughtful responses to challenging and indeed tragic turns of events. She pulls the reader all the way through to what we need to continue life on Earth. And because of that, I believe this book will help many people.

The earnest student in me wore this endorsement like a stamp of approval, as though I was finally, certifiably done with this chapter of my life. It was fitting, then, that as the book went to print late last year, we received notice that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights was ready to issue its decision in Caso U’wa, a human rights case filed by Pueblo U’wa. Decades earlier, Terry had worked on the case—before his murder—alongside one of Joanna’s other devoted students. On the morning of the winter solstice, the Court read its decision aloud to a virtual audience that listened in from offices and homes around the world and villages deep in the Andean cloud forest. After 27 years, we had won. I called my publisher. Then I walked to Joanna’s house to celebrate. It was the last time I saw her alive.

A few weeks later, I joined hundreds of her students at her Berkeley home to say goodbye. We said goodbye to the body of our teacher, the paper-thin skin of her hands receiving our grateful caress. And we said thank you to her family for sharing her so generously with the world.

Who are we without our teachers? When Vietnamese Zen Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh died in 2022, Ocean Vuong reminded the grieving community: “To speak is to survive, and to teach is to shepherd our ideas into the future. The text is a raft we can send forth for all later generations.”

In the slipstream of today’s unrelenting polycrisis, we might find ourselves shocked to realize that we are now steering the raft. But here we are. May we settle into it. May we notice the awe. May we navigate well and together toward the far horizon of the thriving futures that we’ve got to believe are possible. Where our children’s children’s children await, knowing this navigation as the only game in town.

Abby Reyes is an author and recognized leader in driving community climate solutions. Her debut book, Truth Demands: A Memoir of Murder, Oil Wars, and the Rise of Climate Justice, chronicles her pursuit of justice and healing after the murder of her partner and two other land rights advocates in Colombia. She is Director of Community Resilience Projects at the University of California, Irvine, where she supports climate-vulnerable communities to accelerate just transition solutions. A graduate of Stanford University and UC Berkeley Law, she clerked on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, co-chaired the board of EarthRights International, and advises the National Association of Climate Resilience Planners.

Beautiful, and of course it made me cry. I recently learned a lot more about Joanna Macy in the course I'm taking by Fr. Richard Rohr, on his book The Tears of Things: Prophetic Wisdom for an Age of Outrage". Joanna Macy was a force with which to be reckoned, and her work is as important today as it was decades ago. It is timeless and much-needed in this deeply unsettled world we find ourselves in now. I cannot express how much I love the idea of "the Council of All Beings", which is really the only way to access true wisdom and embrace the natural world. Nothing will change until we extricate ourselves from the death grip of our ego and live from our true Self, the one which understands everything is connected.

Wow. This is so deep. I'm a Conservation Assistant (a/k/a volunteer) with the South Carolina Aquarium, and our Resilience initiatives are based on community involvement, particularly with local, underserved communities, and I have so much respect for that kind of work. But the work that Abby does is a step far beyond what I could ever imagine myself doing. I am truly humbled, and inspired.